"They would always touch the Earth"

The Voyager mission's 15-billion-mile journey for some perspective

In the summer of 1965, NASA made a startling discovery. The early space program had already sent two spacecraft — Mariner 2 and Mariner 4 — to conduct flybys of Venus and Mars in order to learn more about their atmospheres, climate, and potential for life. The success of these missions got NASA thinking about ways to learn more about the much-farther-to-reach large outer planets of our solar system (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune — apologies to Pluto).

What they discovered in 1965 was a once-every-176 years alignment of the orbits of these outer planets, such that it would be theoretically possible for a single spacecraft to pass by and take pictures of, all four planets by using gravity swings from each one to propel it to the next. If the probe could be launched within a short window in the late 1970s, the maneuver might be possible.

As it is wont to do, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) got to work, and produced two spacecraft called Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 (NASA decided it would be significantly easier to split the planets up between two probes), which launched twelve years later in the waning summer of 1977.

The two Voyager spacecraft have since achieved mythic status among that sliver of American culture — in which I include myself — with a deep interest in, and borderline obsession over, the majesty and ambition of space exploration. If you’ve heard of the Voyager program, you might know that it’s been pretty much an unmitigated success: both probes got their prescribed looks at the outer planets throughout the 70s and 80s; they made major discoveries about these planets and their moons; and even confirmed the presence of massive superstorms and active volcanic activity on Jupiter, which in my scientific opinion is cool as hell.

Most amazing of all? Both spacecraft have lasted years beyond what the original engineering teams expected of either, and as a result have been able to give us invaluable information about deep space that would have been unthinkable to the probes’ creators. All this time, all these calculations, all those billions of miles traveled and novel discoveries made, were conducted all for under $1 billion dollars, according to NASA/JPL. Since its own launch in 2003 (25 years after Voyager’s), the War in Iraq has a total calculated cost of around $3 trillion, according to scholars at Brown University.

How on Earth — and far from Earth — did NASA do it?

Obviously both probes represent the best NASA had to offer in terms of late 1970s engineering; but much of the credit for Voyager’s longevity goes to engineers here on Earth. Major technological upgrades were made in the late 1980s to NASA’s Deep Space Network to help scientists to hear and understand the signals Voyager 1 and 2 were sending more clearly. More recently, NASA engineers worked what can only be called an astronomical miracle by managing to fix Voyager 1 from 15 billion miles away.

The most ingenious — and wonderfully poetic — of these maneuvers came in 1989 with Voyager 2, and in 1990 with Voyager 1. JPL made the tough decision to turn off the spacecrafts’ cameras to conserve energy for other on-board instruments; they did so because they were able to calculate that the crafts would never pass close enough to take a reliable photo of another major astronomical body again. In the name of science, preserve as many data-collection tools as possible.

For Voyager 1, this decision came as the probe was in a spot in our solar system clear enough to capture not one but six planets from where it stood in the vast expanse of space: Venus, Earth, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, all arrayed about the sun at the same time, posing for one last entry on the cosmic camera roll.

These photographs were taken when I was just over a year old. And yet — I still can’t believe I get to type this — both Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are still operational as of May 2024, almost a half-century after they were launched. As of this post, both probes are sending back signals that continue to teach us about the mysteries of interstellar space.

During that time, both spacecraft — Voyager 1 in particular — crossed a number of major milestones. In 1998, for example, Voyager 1 became the farthest-traveling human-made object from Earth in space, a distinction not likely to be met again anytime soon. On August 25, 2012, it became the first human-made object to enter interstellar space (that is, the first to leave our solar system). In a stroke of you-couldn’t-write-this cosmic poetry, Neil Armstrong — the first human to set foot on the moon — passed away on the exact same day.

Today, Voyager 1 is more than 15 billion miles away from you as you read this (Voyager 2, a cancellable layabout and a slacker to the end, is a measly 12 billion miles away).

For context, that’s about 5 million road trips across the contiguous United States.

Many books could be written about the contributions of the Voyager program to humanity’s understanding and perspective of our solar system, and our place in the universe. But maybe the best-known of them was captured in a single photograph, taken not of a distant, far-flung world that that was previously impossible to imagine; but of a much closer one that we can imagine just by opening our eyes. In the “Solar System Family Portraits” taken before Voyager 1 shut down its camera in 1990, the probe turned its camera finally to its home planet; our beloved Earth. It was a cosmic selfie of sorts, a picture of us from billions of miles away.

If you squint, you can see Earth’s tiny speck in the top-right-center, illuminated by a massive cosmic sunbeam. It was, indeed, a “pale blue dot,” as the late astronomer and master science communicator Carl Sagan put it in his 1994 book of the same name:

Look again at that dot. That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every "superstar," every "supreme leader," every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there-on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

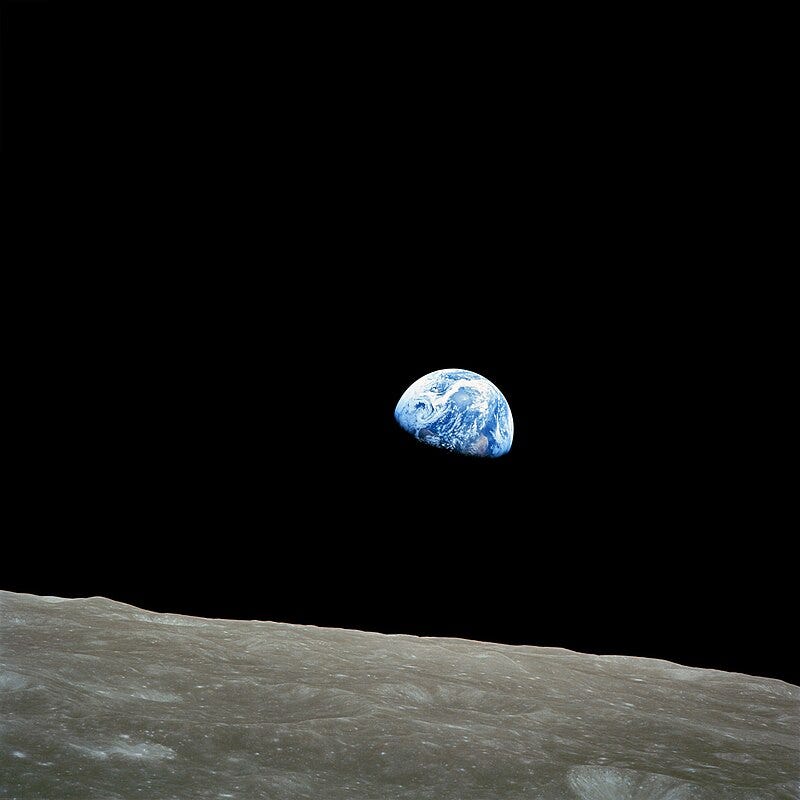

The “pale blue dot” photo from Voyager 1 does lack the sharpness and immediacy of, say “Earthrise,” a photograph taken from orbit around the moon by astronaut William Anders in 1968, during the Apollo 8 mission. I can almost guarantee you’ve seen this one before; it’s a staple of the modern environmental movement, and provoked a massive perspective-shift in how, and how much, we truly consider our home planet. Fifty years to the day after taking the photo, Anders observed, "We set out to explore the moon and instead discovered the Earth."

In terms of its sharpness and majesty, Sagan’s “pale blue dot” image literally pales by comparison. But the vastness of its surroundings, the blink-and-you-miss-it ease with which Earth can be overlooked as a minuscule pixel among a massive blackness, and the striking reminder of the tremendous Voyager achievements, made the image an instant classic. It served, by itself, as a bulletproof justification for the Voyager missions.

However, something strange began to happen after the “pale blue dot” photo was displayed on the wall at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Houston, as a kind of monument to Voyager’s incredible achievement. In a 2020 piece in The Analog Sea Review, the author and nature communicator Trebbe Johnson recounts the mystery:

The JPL employees who had been displaying photos of Voyager's journey added this one to the collection. But then something strange began to happen. The photo showing the pale blue dot had to be replaced again and again, because it kept getting smudged.

Was this a photo-printing error? A prank or a trick? A glitch in the Matrix?

No — according to JPL scientist Candace Hansen-Koharcheck, who worked there at the time, the real reason for the constant smudging became heart-wrenchingly clear: "People would come up to look at it and they would always touch the Earth."

They would always touch the Earth.

I think we can all relate to the photographic vandalism that unfolded at JPL following the release of the “pale blue dot” image. We can imagine walking up, finding the tiny pixel amidst the vastness, and gently touching our finger to it, maybe even rubbing it hoping to feel… something. We take a moment to ourselves, we look, we consider… we touch.

But why? What can explain this instinctual response to seeing ourselves represented so ruthlessly out of perspective? My only real explanation is a kind of instinctual pull towards our home that can’t be easily quantified. Earth animals of all sorts possess difficult-to-explain homing instincts that tend to land them close to home even when they’re forcibly displaced.

Poets of all stripes have known this necessity for reconnection in their bones for centuries. One particular favorite of mine comes from Brad Leithauser; here’s a stanza from his poem “From Here to There”:

There are those great winds on a tear

Over the Great Plains,

Bending the grasses all the way

Down to the roots

And the grasses revealing

A gracefulness in the wind's fury

You would not otherwise

Have suspected there.

Leithauser charts our home planet’s dichotomous tendency to both shock and entrench; to make us feel otherworldly and right at home at the same time.

Touching and feeling the world around you has the benefit of producing surprise, like a sudden “gracefulness in the wind’s fury/You would not otherwise/Have suspected there.” And yet, we only know not to suspect these winds because we know our home so well to begin with. Like any good partner, our home planet surprises us, runs rampant with life and vitality; and though it is painfully subject to our (often terrible, unnatural) whims, it also operates as something much larger than us, and by necessity reflects all the dynamic and unpredictable parts of humanity.

Another one of my favorite examples of this phenomenon from pop culture comes from the movie I love most in this world: Interstellar, the 2014 Christopher Nolan film starting Matthew McConaughey and Anne Hathaway that, to this day, has set the standard for carefulness and accuracy in space-centric movies. In a small, subtle moment that’s inconsequential to the plot, Interstellar captures beautifully the comfort we crave from inhabiting our home, even if we’re doing so from just outside the rings of Saturn:

It’s quiet, but I find it deeply moving: Romily, the astrophysicist played by David Gyasi, has awoken form a years-long sleep to find himself within view of Saturn, millions of miles from home, and like any normal human being, he’s deeply freaked out by that. To recoup his nerves, Romily finds some comfort in the sounds not just of Matthew McConaughey’s southern drawl, but of crickets, rainfall, and a looming thunderstorm.

The core motivation for most of the characters in this film is not “manifest destiny”-style exploration, or the cool physics of space, but rather the chance to save their home the loved ones who inhabit it; even the stormy, wet, complicated parts of it.

What a lovely change from the eye-rolling predictability and dark, inevitable doomerism that we see in our politics, our culture, and particularly our online lives. Indeed, it feels possible to me that our homing instinct is firing with more urgency than ever in our modernizing, thoroughly de-placed culture. This helps explain findings in my own research that Americans are craving now, more than ever, a locally-tied politician to lead and represent them.

As I’ve written about before, nothing literally displaces us more than the Internet. As we venture into a digital world that promises expansion from, and ignorance towards, our tangible world, we are called to reengage. Here’s Trebbe Johnson again, from her piece on the disappearing blue dot at JPL:

This drive for intimacy with the planet of our birth begins in infancy and never leaves us; we just develop the habit, as we grow older, of ignoring it. In order to retain our sanity in challenging times and do our part in keeping the planet healthy, it is essential that we relearn the knack of touching the Earth.

This is a lesson we might all feel like we understand instinctually. It’s a modern-day manifestation of the intuitional pull we have towards home: that clearly, the way out of this displacement we’re all feeling is to turn back towards the only known planet on which humans are known to be able to survive.

Even so, it’s tough to deny that the Voyager missions — admirable and pathbreaking though they might be — are clear efforts to get as far away from Earth as possible. And it’s not the only major effort to do so. Lots of attention has been paid, for example, to Elon Musk’s ongoing quest to colonize Mars, despite his constantly getting distracted by the much more attainable and deeply dumb quest to ruin social media. Musk has made the case that because of how badly we’re mistreating our home planet, we’d be wise to essentially “back up our hard drive” by settling elsewhere to make sure humanity doesn’t completely disappear if we really screw things up here.

I have a confession to make: despite his recent history, I’m not convinced that these efforts are solely an Elon Musk vanity project. Inhabiting other planets — especially ones that don’t currently have advanced life — is not, to me, an inherently bad idea. These are efforts to explore, to learn, to push the boundaries of what’s possible. It’s not a popular opinion in the age of increasingly-concerning advances in artificial intelligence; but I believe we should be doing more, not less, to examine exactly what we would need to do in order to live comfortably in places other than the bountiful, miraculous Earth we’ve been given, and which we are continually, willing, tragically wasting.

So if I may (as it’s my Substack newsletter), I’ll split the difference: let’s discard the very “online” tendency to frame this debate as “aim for the stars and colonize everywhere” versus “dismantle NASA and dedicate the funds only towards reducing greenhouse gases.” We are a country — and in the scheme of things, a world — clothed in immense wealth and opportunity, and we can surely do reasonable, responsible, ethical versions of both of these things. We can explore other worlds and reach beyond what we thought was previous possible; and we can save the Earth we have with the tools we already have available. In both instances, we are limited only by our own short-sightedness and stupidity.

The promise of space travel, of the Webb telescope, and of so many recent magnificent discoveries and astronomical events enjoyed by us normals here on Earth, all shout to us that there’s so much more out there than what we know, and we’d be foolish to ignore it. But so too would we be foolish to ignore what Carl Sagan said in his reflection on the “pale blue dot” photograph: “Like it or not, for the moment, the Earth is where we make our stand.” We are not Martians, and we, unlike Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, are not interstellar. We are here.

It’s here that the Voyager missions offer us a path forward. Voyager began here, on Eath, as a dream; an impossibility; dead in a decade. But NASA made the mission happen: Both launches went off successfully; they saw the planets they were supposed to, and they ventured beyond our wildest dreams. They show us what there is to gain from Voyaging with a capital “V”.

Before it kept moving beyond our imagining, though, Voyager 1 was instructed to look back towards its cosmic home, and take a picture to remember where it came from.

It helps us remember, too. Every once in awhile, we need a broader — sometimes a much, much broader — perspective to remind us what we’re fighting for. “That’s home. That’s us.” The instinctual, primordial pull we have towards the earth is exactly what drew us to the tiny dot on the farthest-away picture ever taken of our beautifully massive yet minuscule planet.

Your nephew is constantly talking about Interstellar, though I don't believe I've ever seen it. Despite the disastrous shape that the national debt is in, it seems prudent to keep reaching for something out there beyond our own spec of dust.

Beautiful, thank you. You know what else puts things into perspective? When the earth is needlessly demolished to make way for a new hyperspace bypass. (I’ve been rereading Hitchhikers Guide and it was kind of funny how much it came to mind while I reading your piece, despite the vast difference in style—when it comes down to it I think that series is really about the same thing.)