Taylor, Travis, and the rest of us, singing along to the same song

We shouldn't all like the same things all the time; but once in awhile, we need a monocultural moment

Like 123 million other Americans, I watched the Superbowl a couple of weeks ago with my wife and my sister-in-law’s family. Despite the snooze of a first half, we enjoyed the exciting finish; the Taylor Swift facial expression analysis; the Usher of it all.

As we turned onto our street after the game, we spotted quite a few of our neighbors driving home as well, pulling into their driveways after (presumably) taking in the game too, with their own family and friends. Observing this, Keara turned to me and stated, quite plainly, “Isn’t it nice that for once, we were all doing the same thing at the same time?”

I’m proud of my PhD, but you don’t need a political expert to understand that we’re a deeply polarized country going through a deeply polarized period of politics. Our two political parties and the people who vote with them are very far apart from each other, drifting ever-further towards two poles (hence, polarization) on opposite ends of the spectrum. In their issue positions, for example, Democrats are moving increasingly to the ideological left, and Republicans moving even further to the extreme right.

These divisions have extended to less apparently political, and more concretely cultural ones: where we live, what we watch on TV, the places we shop, and even which music we listen to are increasingly divided along these political boundaries.

When our culture isn’t split cleanly in two, it’s split roughly into a million pieces. As humans, we’re made up of a bunch of important identities, many of which go far beyond politics. These identities—race, gender, religion, geography, the list goes on—were important before our current left-right divide, and will be important long after it’s gone. They each produce their own cultural touch points and symbols that have unique and important meanings within those groups. By definition, these touch points aren’t—or, it’s argued, shouldn’t be—available to out-groups; and so this is also where we can find the important, often-righteous, but sometimes-exhausting debate over cultural appropriation.

At any rate, one end result of these cultural separations—whether based on partisan political polarization, or on other meaningful identities—is a lack of commonality in many of the cultural touchstones that mean the most to us. I can’t be the only one who finds this to be a natural but frustrating part of life. Isn’t there anything—literally anything—we can all like together?

Taylor and Travis to the Rescue

It turns out that, even as polarization and cultural division continues to worsen, there are still a couple of American institutions that have not quite universal appeal, but certainly something close to mass appeal.

One, I was surprised to learn, was football. I grew up enjoying football (if not caring about it all that much), but always understood it as a fairly Republican-coded sport. Turns out I was wrong. Surveys by Ipsos and Sportico from 2023 report that “44% of Democrats said they were fans of the NFL and 45% of Republicans said the same thing — a rare area of partisan common ground.” In addition to its uncommon cross-partisan appeal, NFL football also has pretty unparalleled mass appeal. Of the top 100 most-viewed broadcasts in the country in 2022, 82 were NFL games. And historically, 29 of the 30 most-viewed broadcasts in American history have been Superbowls, and this most recent one decisively took the top spot (the 2022 Superbowl is #2). For this reason, and for better or worse, the NFL is inseparable from America’s national identity.

So how could you even go about raising its stature even further? By pairing one of the NFL’s most likable, talented, and charismatic stars with possibly the most successful pop star in history.

In 2023, Taylor Swift broke just about every record imaginable to prove her massive appeal. The U.S. leg of her Eras Tour by itself became the highest-grossing tour of all time, taking in well over $1 billion. She secured a spot as the female artist with the most U.S. number 1 albums in history, and has spent more weeks at number 1 than any solo artist in history, surpassing Elvis Presley. One of those albums, Midnights (2022), earned her a record-breaking fourth Grammy award for Album of the Year, vaulting her above an already-elite class of three-time winners (Paul Simon, Stevie Wonder, and Frank Sinatra). The list goes on: long story short, many, many people (including me) like this person and her music.

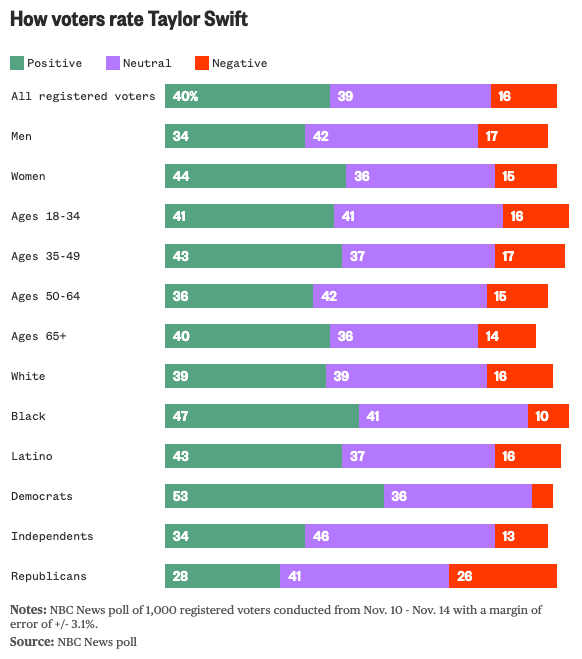

Taylor’s appeal is broad, but is it diverse? Are Swifties legion, but uniform in their demographics or political leanings? An NBC News poll from last year says no. Taylor is viewed either positively or neutrally by vast majorities of pretty much every meaningful subset of Americans, and her “net favorability” (the percentage of Americans who view her favorably minus the percentage who view her unfavorably) is positive among all of these groups. Like the NFL, Taylor’s appeal seems to cut in many ways across party, age, race, and even gender.

In a way, Taylor’s cross-partisan appeal is more impressive than the NFL’s, considering she openly endorsed Democratic candidates for U.S. Senate in 2018, as well as the Biden/Harris presidential ticket in 2020. And it’s true that Democrats like her better than Republicans. But, despite the deeply weird MAGA meltdown ensuing over her and Travis for reasons that are still unclear to me, she is—technically speaking—a distinctly non-polarizing figure. This is true in the sense of our two-sided political cultures; and also amongst the many microcultures that emerge from identities like race, gender, and geography.

As a result, we probably shouldn’t be all that surprised that the Travis Kelce-Taylor Swift romance has entranced us so. Kelce and the NFL, plus Taylor and her multi-genre music of unparalleled popularity, combine to create a cultural crossover moment so wonderfully flat and relatable that it’s tough to hate it—and importantly, not possible to “appropriate” it—precisely because it belongs to just about everyone.

Should we all like the same things?

Are we wrong to crave moments like these, even if they bring huge, diverse collections of people together? Maybe not, but there are good reasons not to put all our cultural eggs into one big basket of mass appeal.

First, the cultural touch points that differ between (for example) racial and ethnic groups matter enormously to each group and create meaning, camaraderie, and commonality within the group even while making them distinct from others. The same is true within our distinctive, if fluid, gender identities; and certainly within specific places (nations, states, cities, etc), where the shared cultures, languages, and institutions that make a place unique can create meaningful and lasting in-group bonds in those places even while (by definition) separating that group from others.

The Taylor and Travis moment we seem to be having is often referred to as “monocultural,” which means exactly what it sounds like. It’s a single cultural instance that appeals broadly across an entire people. The term comes from monoculture farming, which involves planting identical crops across an entire farming space for the sake of efficiency. Research, as well as the lived experience of small-farm advocates like the beloved writer and poet Wendell Berry, have found that monoculture farming degrades the soil we need to grow food and has negative downstream effects on the broader environment, as well as farmers’ ability to grow more diverse crops in the future.

The same goes for social and political ideas, of course. If we all believed and liked the same stuff, public life sure would be easier and much more efficient. It would also be boring, devoid of innovation and vibrancy, and definitely worse. Competition between ideas and diversity of thought (what we commonly call pluralism) is the bedrock of a healthy and resilient political culture, just as it is for a well-balanced crop yield. So, we might be wary of relying only on de-polarizing, easy-to-digest social culture like Travis and Taylor to enrich us.

Finally, monoculture in farming and in society are both susceptible to the same worrying tendencies of our capitalist economy. Berry and others write persuasively about the intense pressure to grow only monoculture crops leading to the ruin of small farms economically, usually in favor of giant agribusiness conglomerates who can mass-produce these crops more efficiently, and of course at great cost to our environment.

On the social side, I’m all in favor of a sales spike in Travis Kelce jerseys, but there is something deeply off-putting about the sick rush of soulless brands to literally capitalize on something that’s just supposed to be a fun thing for us all to enjoy.

It’s an inevitable part of our economy that demands our attention. There’s a reason Superbowl commercial spots cost millions of dollars: appealing to as many people as possible is good business. Is that what we really want as the basis of our shared cultural life?

Counterpoint: Please just let us have this

All of these warnings against monoculture are not just important to consider, but crucial if we’re going to have a healthy and sustainable society. We need as much diversity of opinion, politics, taste, and culture as we can possibly take.

On the other hand, our level of cultural fracture has hit critical and unsustainable levels. We are more separate and alien from each other than we’ve ever been, and it’s become more and more difficult to find common spaces for us to inhabit in our politics, our personal lives, and our culture, too. There is a social cost to this literal disintegration that is tough to quantify, but that I’m sure is massive.

This fracture has been (shocker of the century) horribly exacerbated by the Internet, and by the magic glowing rectangles that deliver it to us. Far from bringing us together over vast space, the blessing of an Internet connection has brought with it, ironically, a curse of separateness and disconnection that seems to get worse all the time.

And so, our culture—or at least the web’s projection of it—can feel lonely and alienating, defined by its fragmentation rather than by its “Familiarity,” as goes the Punch Brothers song (Apple Music/Spotify) off their 2015 album The Phosphorescent Blues:

We lie in bed

The wireless dancing through my head

Until I fear the space between my breath

I see an end where I don't love you like I can

'Cause I've forgotten how it feels (amen)

To love someone or thing for real (amen)

So, darling when you wake, remind me what we've done

That can't be shared, or saved, or even sung

“Familiarity” is probably the song I would take with me to a survivalist bunker if I were forced to choose one. Besides the pitch-perfect composition, what I love about this song is not just its lyrical diagnosis of the problem (late-stage loneliness brought on by technology) but its prescribed solution.

The song features a group of friends at a bar, haunted by their isolation, but brought together briefly by a song on the radio they all know.1 It may not be universally beloved or respected (nothing is), but it is universally known, and that’s what matters. It’s a space of mutual understanding and presence that we can all arrive at together, enabling us to “explode out of [our] phones” and embrace the togetherness that the song is offering; even if you, the individual, aren’t wild about the song:

It's on

Pretend you love it because you love them

As you explode out of your phones (amen)

To make some music of your own (amen)

Thanks to the jolt and the joy of finding something they can all relate to, the friends are thrown from their isolating technological reverie into a collective revelry, as they “lift [their] voice” in a kind of prayer to sing it together in the bar.

A call to prayer, or the last for alcohol

We didn't care; we knelt and bowed our heads

Or did we dance? Like we might never get another chance to disconnect

We've come together

over we know not what

to say I love you

The dream, for these bar patrons, is to “disconnect”—not from each other, but from the flood of discord and fracture fed to them through their phones. The fact that they cling, every one of them, to a song none of them love but which all of them know, puts on display their desperation for a moment of mutuality, and their dissatisfaction with the alienation they’re supplied by the buzzing cacophony in their pockets.

Although “Familiarity” is more of a commentary on technology than it is on broader culture divisions, I think it’s apt here, and can help us understand why a phenomenon like Taylor and Travis (I can’t in good conscience call it “Swelce”) has arrived as a kind of balm for the country in a time of peak disunity.

Like the song in the bar, the Swift-Kelce romance is not apparently complicated. Boy loves girl, girl loves boy, both are at their respective pinnacles of professional achievement, and both seem to share an adorable and mutual respect for each others’ careers.

This story is nice, but it doesn’t have to be a major source of self-esteem or personal well-being for people outside of these people’s immediate circles. Although I’m sure it’s not low-stakes for the two lovebirds, it is for the rest of us. For all but the most deranged and conspiratorial among us, it’s also disconnected from politics and hot-button issues — in a way, it has to be in order for us all to like it. This romance is not going to heal our nation’s deep partisan wounds, nor will it (nor should it) distract us from the important differences we do have that need dealing with.

What this love story can do, though, is bring as many of us as possible into a mutual conversation about a pretty singular cultural courtship. Why not pause the hostilities and trade a “how about the two of them?” with a co-worker about a couple of attractive, over-the-top virtuosos falling head over heels in love on the world’s biggest stage?

Thanks for reading today’s post! I have just one more thing to share on the political science end of things. If you’re in any way interested and have a free hour to spare, you might enjoy this discussion I participated in the other day with the amazing Stefanie Lindquist, Dean of the Washington University-St. Louis School of Law, in a collaboration with The Conversation, a fabulous outlet I write for with some regularity. The discussion, which covered a range of questions on “Democracy in an Election Year”, was moderated by the always-sharp Naomi Schalit, Democracy Editor at The Conversation.

Maybe it’s “Don’t Stop Believin’.” Maybe it’s “Can’t Touch This.” Hell, maybe it’s “Shake It Off.”

The NFL has never ceased to amaze me in its mass appeal. And the Super Bowl time slot is virtually as sacred of a time slot on calendars as New Year’s Eve, July 4th, Christmas Eve. Perhaps every holiday other than thanksgiving and Christmas (both of which I spent considerable portions of watching NFL football).

But you know I’m all for diverse interests - as much as I follow and discuss football with folks (it’s likely my widest circle), I eagerly engage with people on software engineering, personal finance, youth sports parenting, international travel planning, home automation, MLB, and of course theatre every now and then. I appreciate the different relationships I have surrounding each of these, although interestingly not a lot of them overlap.

It was my first Super Bowl and I enjoyed watching the sport on TV, especially as I've been to the Allegiant Stadium in Las Vegas for a College Football match. I like the way you weave this event into your commentary on the polarisation of US politics, Charlie. I also took in your conversation with Stefanie Lindquist, which was very interesting. Thanks again, for a super informative and lively post.