State legislatures are hijacking geography to break direct democracy

Direct democracy isn't always great; but when state legislatures play fast and loose with geographic representation, voters lose out

Hey all—I’m beyond grateful for the support I’ve gotten for this newsletter so far, and am really eager for it to expand into new and exciting places. So if you’ve so far just been coming across this on Instagram, or Bluesky or wherever else, I’d really love it if you’d consider subscribing to get new posts directly in your inbox or through the Substack app.

If you’re already a subscriber, it would mean the world to me if you’d consider forwarding or sharing this with someone who you think might enjoy it. Giving the post a “like” by hitting the heart up and to your left is also super helpful, even if you don’t have a Substack account. Thanks!

We’ve already covered in this space how often geography is used as a handy excuse to transgress on Americans’ right to vote: for example, how the Electoral College is leaned on as a safeguard for states, when all it really succeeds in doing is screwing up representation in presidential elections.

Many propose that the antidote to this kind of Rube-Goldberg-machine method of making political choices is a reversion to the truest selection method we know of: direct democracy, which appears in American states in the form of ballot initiatives and popular referenda—we’ll get into the differences shortly. But the gist of it is: Let the people vote on whatever’s on the table. If a statewide proposal to legalize marijuana it supported by some majority of the public, it passes; if it doesn’t, it doesn’t. No need for weird intermediaries like delegates, electors, or even state legislators (God love ‘em); instead, the people decide.

Regardless of whether direct democracy is a good idea, we know that if nothing else, it’s suppose to be simple. But modern state legislatures are making it purposely complicated. They’re using a warped version of place representation to stop it in its tracks, in places where it could have the greatest effect. Let’s get into it.

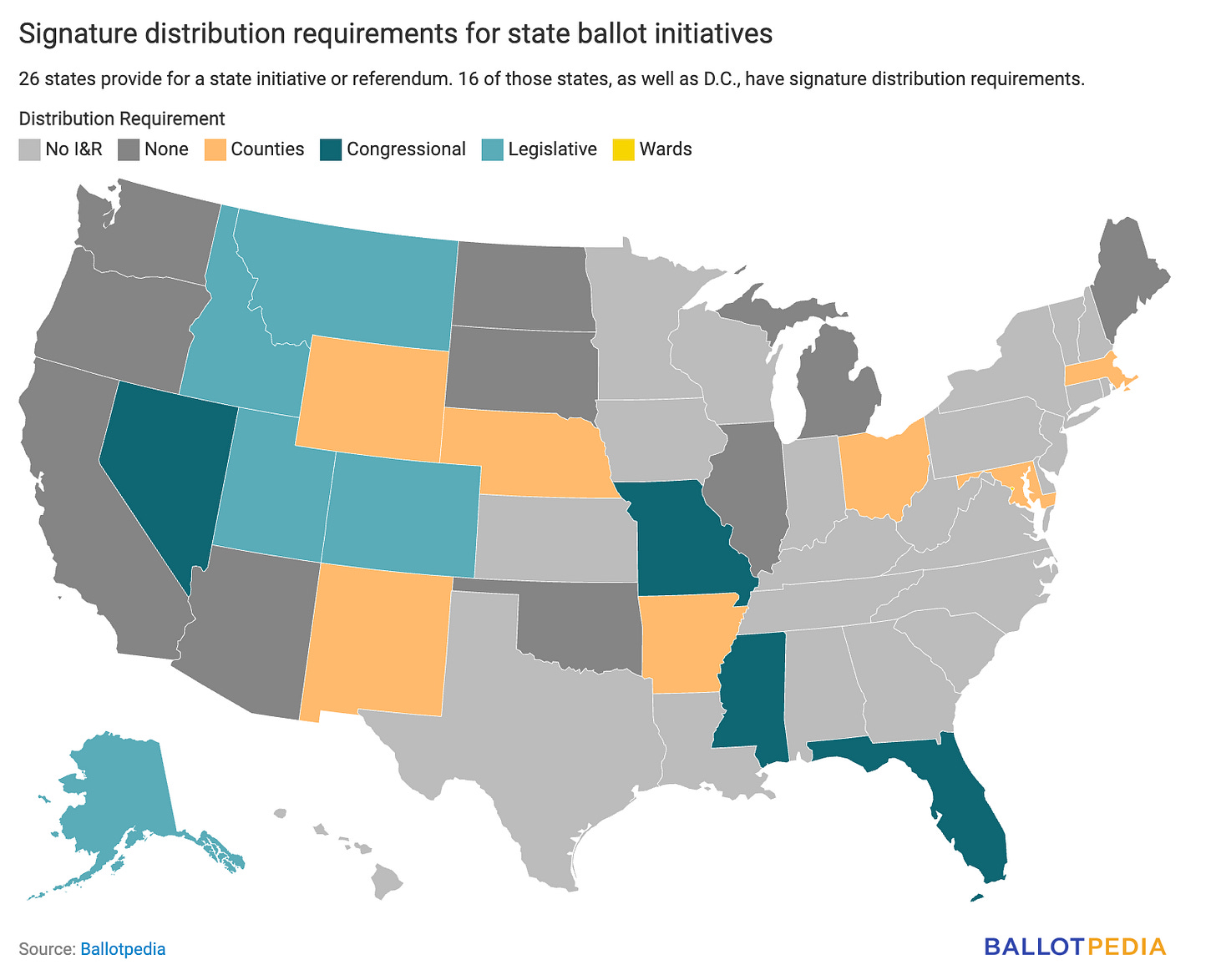

It’s very possible that in your lifetime you’ve voted for (or against) a particular policy proposal, rather than a candidate, on your election ballot. As you can see in the below map (courtesy of Ballotpedia), many states allow voters to weigh in directly on critical issues on the same ballot they use to choose members of Congress and presidents; this is what we usually mean when we refer to “ballot initiative.” These tend to be the most common and attention-getting forms of direct democracy. You’ve probably heard these referred to by their “proposition” shorthand—Prop 1, Prop 2, etc.

Some states let voters weigh in to reject something the state government recently passed, which are called a “veto referendum” (I’ve always loved the “lol thx, but no” energy of this one). It essentially gives voters the same power most governors (and all presidents) have in the legislative process.

Others still let voters pass amendments to their state’s constitution using this process. All told, about 26 states allow for some method of direct democracy.1

But where these states vary even more, and where today’s “place” issues lie, is with the requirements these states have for actually getting these propositions on the ballot in the first place. You may have seen folks in your local community with clipboards and matching T-shirts collecting signatures for one of these ballot questions—say, one looking to decriminalize marijuana, or raise the state’s minimum wage.

States have different thresholds for how many unique voter signatures are required for a question to get on the ballot—usually, they require a certain percentage of the state’s voters to lend their signatures to the proposal in order for it to get on the ballot. These percentages are usually in the range of 5-10% of the state’s voting population.2 They also differ by question type; for example, because it’s a more drastic and difficult-to-reverse step, proposed state constitutional amendments tend to have the highest thresholds.

It’s a legitimately good thing that we have these thresholds, and that they aren’t too low. If we didn’t, then we’d be seeing hundreds of propositions on our ballots every year, and nobody has time to stand around all day in a voting booth ticking boxes. It’s hard enough to get people to vote as it is. And because they usually appear last on a voter’s ballot, propositions are already susceptible to what political scientists call “rolloff”—when someone marks their vote for high-profile races like President, Governor, and Congress, but then leaves later questions on their ballots blank.

But in many states, the requirements don’t end here. Let’s use my home state of Idaho as an example. Idaho has a signature requirement of 6% of eligible Idaho voters statewide; but they also require that these signatures reach the 6% threshold separately in at least half of Idaho’s 35 state legislative districts. This is what’s called a signature distribution requirement, and most states have them in some form on top of the standard statewide threshold.

So why do states add these hurdles on top of everything else? The idea is that all of a ballot question proposal’s signatures shouldn’t just come from one small part of the state. If a policy question is going to appear on the ballot for voters to weigh in on directly, it should spring organically from a diverse set of the state’s citizens, and not just from a concentrated group in one or two parts of the state.

The problem is, some states—including Idaho—have hijacked these requirements and taken them to the extreme to make ballot initiatives functionally impossible to propose; and they’ve done so in an overtly partisan way.

After the passage of the Affordable Care Act (also known as Obamacare) in 2010, many states took advantage of the provisions in that law that expanded the availability of federal funding for Medicaid, the program in place to provide healthcare coverage for low-income Americans. But many states did not. These were primarily Republican-controlled states who were ostensibly concerned with growing the national debt, but who also just didn’t want to be seen as participating in the implementation of Barack Obama’s signature legislative achievement.

Not surprisingly, Idaho was one of those states. For more than half a decade, Idaho and other states refused this federal funding while the rest used it to expand coverage for underserved residents of their states. Eventually, a group of concerned Idahoans called Reclaim Idaho had enough, and began organizing to get Medicaid expansion on the ballot in its own right, since the state legislature and Governor weren’t willing to take it up. They went to work gathering signatures, enough to satisfy Idaho’s overall requirement (6% of the state’s voters) and the distribution requirements (6% of voters in at least half of Idaho’s state legislative districts). They got the signatures; they got Medicaid expansion on the ballot; and in a deep red state, the measure passed with 61% of the vote in 2018.

Since that time, the state legislature in Idaho decided this wasn’t okay, and has tried—again and again—to substantially tighten the signature distribution requirements for ballot initiatives in order to ensure that progressive priorities like Medicaid expansion aren’t adopted again in this way. In a bill proposed during the 2019 legislative session (just after voters passed Medicaid expansion), the legislature pushed a bill that would raise the signature threshold from 6% of the state’s voters to 10%; and the number of state legislative districts the signature-gatherers need to pull from was upped from 18 to 33. A 2021 bill, which actually passed, raised this threshold even higher to all 35 state districts. In short order, the law was struck down by the Idaho Supreme Court.

Finally, just this year the legislature attempted the even more significant feat of amending the Idaho’s constitution to include the 100%-of-districts requirement. That, too, was shot down by moderate Republicans: “Legislators who opposed Senate Joint Resolution 101a,” reported Clark Corbin of the Idaho Capital Sun, “said it would have made it functionally impossible to qualify a ballot initiative or referendum for the ballots and given any one legislative district ‘veto power’ over the other 34 districts.”

So here in Idaho, we’re back where we started, for now. And it really does matter that none of these proposed changes have gone into effect, because Reclaim Idaho and others have continued their push for additional reforms. For example, there is campaign underway for the 2024 election that would establish open primaries and ranked-choice voting in Idaho, a proposal backed by former Governor Butch Otter (R), but opposed by Idaho’s Republican Party chair.

I may be cynical, but I have a hunch that the Idaho’s legislature’s sudden interest in the ballot initiative process isn’t an expression of deep constitutional thinking about place representation. They don’t like that progressives have finally gotten some policies they want, plain and simple. As a result, they want to change the rules to make this route of representation more difficult, and distribution requirements are how they’ve chosen to do it.

Even so, this doesn’t mean we shouldn’t revisit how we do direct democracy. I completely agree, for example, that it shouldn’t be too easy to get things on the ballot. One useful case study is California, which has a statewide signature requirement that shakes out to about 2.5% of the state’s registered voters, and zero geographic distribution requirements. The result? It had 13 statewide initiatives and referenda on the ballot in 2020, and already has 11 slated for 2024. I may just have a short attention span, but this feels like too many, even for a huge state like California.

Distribution requirements aren’t a bad thing; but they should be done smarter and fairer. One issue has to do with which kind of geography we’re talking about, a question which I’d wager most state lawmakers are not thinking all that deeply about. For example, back in the 90s, Idaho required that signatures meet their 6% threshold in half of the state’s counties—not state legislative districts. Many states, including our neighbor Wyoming, still do it this way. Others use federal congressional districts as the basis for distribution requirements (see below).

Each comes with its own drawbacks. A solid proportion of many state’s counties, for example, are very rural and have very small populations (sometimes in the hundreds, not thousands), making it difficult to gather signatures in those places. This is the basis on which Idaho’s own county-level requirements were struck down as unconstitutional back in 2001: The judge ruled that "...it easy to envision a situation where three-fourths of Idaho's voters sign a petition but fail to get it on the ballot because they could not collect 6 percent of the vote in rural counties." In other words, you don’t want these requirements to give a tiny part of the state veto power over all the rest.

But using legislative districts comes with its own challenges. They tend to be equal in size, sure—but they can also be gerrymandered to hell and back, giving really conservative districts a similar veto over more progressive proposals (as the case would be in Idaho), or vice versa.

Whatever form of geography you use, though, there are simpler ways to prevent these kinds of issues. You don’t want tiny slivers of states to have veto power over these proposals, but you also don’t want all the signatures coming from one part of the state. States like my former home of Maryland prevent this by requiring only that most of a proposal’s signatures can’t all come from one single county. To me, this seems like a pretty good compromise to ensure that, for example, California’s initiatives don’t all just stream in from Los Angeles or the Bay Area.

On top of all this, I’m not that sure direct democracy is all that useful to begin with. For example, pretty much nobody—political scientist or not—has been able to articulate for me a hard-and-fast rule for what should be decided by direct democracy, versus what state legislatures should deal with. And in the absence of such a rule, we end up with significant policy confusion at the state level.

Second, a ton of ballot initiatives are so confusingly worded and cover such esoteric issues that it’s not reasonable to ask regular voters (much less political scientists) to have clear opinions about them. One California initiative from 2020, for example, would have “require[d] all new state taxes to be enacted via a two-thirds legislative vote and voter approval and requires all new local taxes to be enacted via a two-thirds vote of the local electorate.” Um… ok!

Finally, at the end of the day, most people’s opinions about direct democracy probably correspond with whatever’s being voted on: it’s awesome if it results in something I like (the voting rights proposition Michigan passed in 2022), and it sucks if it’s something I don’t like (the heinous same-sex marriage bans passed in multiple states in the mid-2000s).

But: If state legislatures want to get rid of direct democracy, they should just suck it up and do it. And in the meantime, if they’re too scared of the voters to actually do this (as I suspect they are), I’d appreciate it if they stopped hijacking important ideas about place representation to pull the rug out from under their constituents.

The direct democracy phenomenon is interestingly very much a West Coast thing. It had never traditionally been part of the American policy process for the first part of our history, which explains why those stodgy colonial East-Coasters have very little appetite for it. But, as we see with other electoral reforms like all-mail balloting, Western states seem to have a slightly more adventurous political culture.

In many cases, states instead use as their denominator some similar percentage of the total number of voters in the most recent election for governor or another statewide office—since a solid portion of most states’ populations simply (sadly) don’t vote in state elections.

You laid out some compelling arguments for a whole host of POVs. This really feels like a Goldilocks approach is the right one. IMO something like 5-7% of registered voters, and minimum of 50% of counties getting x%. I agree it cannot just be a minimum threshold across the state if you have big cities that could easily get these numbers (LA, NYC, Chicago, Atlanta) that aren't close to representative of the state. But having extremes of ALL counties, or (worse) ALL legislative districts seems like a bridge too far (particularly for rural large states like yours, Wyoming, Dakotas, etc).

I live in MA and we always have 3-5 ballot initiatives which I mostly enjoy, but I do some pretty decent research before filling out my ballot or heading to the polls. However, I realize I am in the minority of voters. The questions can often be confusing, and cannot be boiled down to a scary 30 second ad a voter might see a week before the election.

When you figure out the right answer, be sure to let the Idaho legislature know. They appear to be quite open to change the past few years