The Electoral College is a disaster for place representation

In addition to all the other well-known reasons it sucks

I doubt I need to work all that hard to convince many of you that the Electoral College is, with respect, a dumb idea. It makes little to no sense to most Americans. It leaves open too many doors to the kinds of norm-violating, constitution-desecrating shenanigans we witnessed in the aftermath of the 2020 election. And most obviously, it creates the opportunity for a candidate to get fewer votes than their opponent on a nationwide basis, and yet still win the election to a nationwide office.

This can lead to a deep, and deeply understandable, sense of incredulity. Take, for example, the reaction of this disgruntled Republican voter on election night 2012, when it looked briefly like Mitt Romney might win the popular vote, but lose the Electoral College:

“[Barack Obama] lost the popular vote by a lot and won the election. We should have a revolution in this country!” the future president, who himself fulfilled exactly these criteria four years later, added in another since-deleted tweet; “More votes equals a loss … revolution!” I guess I’m not as much of a revolutionary as Donald Trump, but his frustration at the time makes undeniable sense, even if it was misplaced by the end of the night (Obama did, of course, end up winning the popular vote, too). This kind of outcome, which has been realized twice in the last six presidential elections, just isn’t fair, period. In a modern democracy, it defies common sense for the candidate who gets the most votes to lose the election.

Despite these concerns, proponents of the Electoral College are fond of asserting that the system fulfills an important function of representation that needs to be preserved. Namely, it helps make sure that certain American places don’t get forgotten by the process, which (it’s argued) they would if we got rid of the Electoral College in favor of a system that simply tallies votes for president nationwide. Doing so would shift all the focus to individual voters rather than the unique places they hail from and identify with. Instead, by raising the stakes of winning more geographically separate states by assigning electoral votes to them, the Electoral College spreads out the support a candidate needs to win, and defends against a situation where a few dense pockets of urbanites have a monopoly on who becomes president.

I do quite a bit of research about the importance of places to political representation in America, so I’m as on board with this goal as anybody. The problem? Not only does the Electoral College not achieve good place representation; it’s actively, uniquely, and spectacularly bad at it. Let’s dive into just a few of the big reasons why.

It does a really bad job of representing states

First, Electoral College defenders argue that the institution is crucial because it acknowledges that in addition to a nation of individual voters, we are a union of states with distinct identities, industries, and legacies. These states are a meaningful unit of representation in and of themselves, and not just as the sum of their voters. By letting states be electoral prizes by themselves, rather than just a cog in the big American political machine, we help preserve states’ rights and identities. More materially, the system incentivizes presidential candidates to pay special attention to the unique needs of each state.

This argument resonates with me. I mean this sincerely. Americans do care about their home states, and states really do have unique needs that make this kind of dispersed geographic representation a worthy goal. And if the Electoral College actually achieved this goal, it might even be worth the occasional popular vote/electoral vote mismatch of the sort we saw in 2016 and 2000.

Unfortunately, the Electoral College falls laughably short of this goal and is impressively bad at spreading out attention across the states. Even a casual observer of presidential elections probably knows that under our current system, presidential candidates very much do not visit all states equally. Instead, they spend their time exactly where you’d think: competitive “battleground” states.

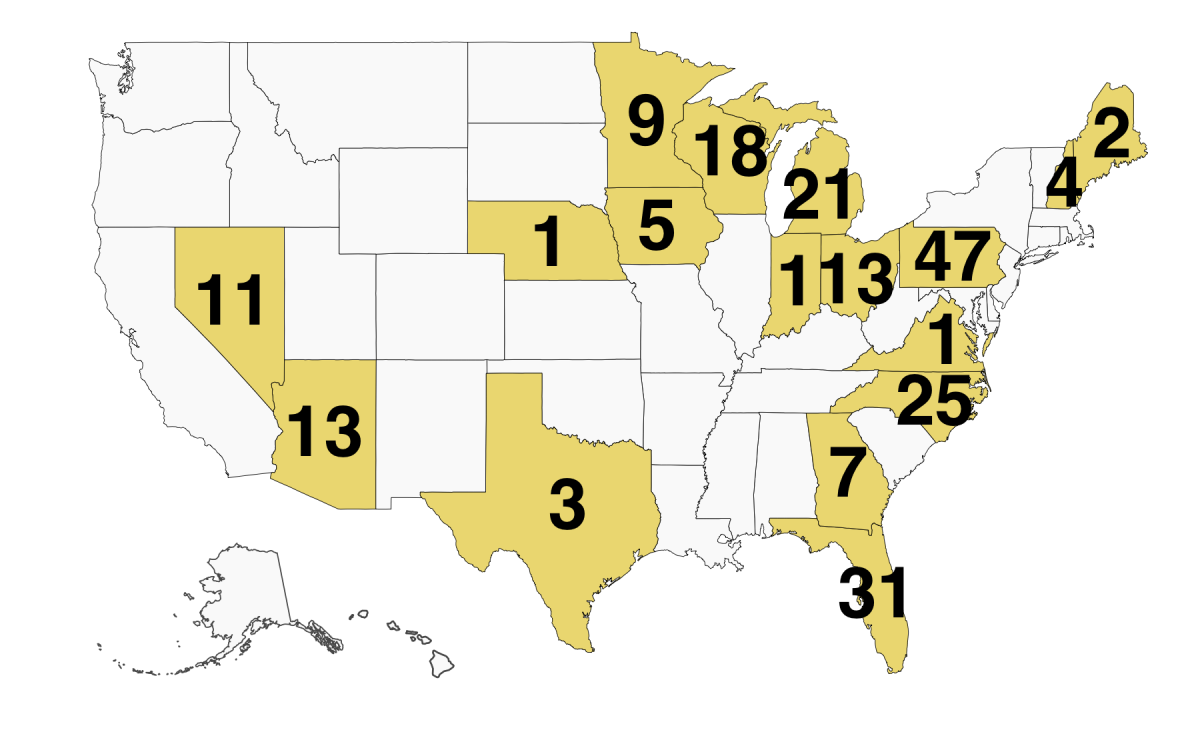

The map below, courtesy of Fairvote’s Presidential Election Event Tracker data, illustrates how many campaign events the two major-party candidates and their vice presidential nominees spent in each state in 2020.

The map speaks for itself, but this analysis from NationalPopularVote.com puts it in stark terms:

12 states… received 96% of the 2020 general-election campaign events (204 of 212) by the major-party presidential and vice-presidential candidates... All of the 212 events were in just 17 states, meaning that 33 states and the District of Columbia did not receive any general-election campaign events at all.

This wasn’t a fluke, either. In 2016, 12 states accounted for 94% of these campaign appearances. In 2012, it was 100%.

The story is the same for spending on campaign advertising. According to an analysis by NPR, 9 out of every 10 dollars spent in 2020 by the candidates was deployed to just six swing states. Most of the American population, and the vast majority of American states, got radio silence in terms of direct communication from or appearances by the candidates.

Why? Because most states allocate their electoral votes in a winner-take-all fashion—meaning, Donald Trump gets all 40 of Texas’s votes whether he wins by 1 vote or 10 million. As a result, candidates have no incentive to spend time either in states they can’t possibly win, even if a lot of people cast votes for them in those places; or in states they have in the bag, because it’s a waste of time and effort. Instead, they camp out in swing states where their appearances might feasibly tip the balance.

These battleground states are perfectly lovely states. Pennsylvania, Arizona, Georgia, Nevada—all gems. They deserve attention. But surely they don’t deserve 96% of it. If the main function of the Electoral College is to ensure that a variety of states get their due, it’s not going great.

Would big cities dominate a world without the Electoral College?

Here’s the thing, though. Even if the Electoral College isn’t ideal at maximizing state representation, it doesn’t mean that the most common proposed reform—switching to a simple nationwide popular vote—would do any better. Yes, candidates spend all their time in swing states now; but at least these states are a reasonable demographic cross-section of the population. If we got rid of the Electoral College, candidates would no longer have any incentive to campaign in rural or otherwise depopulated areas.

This is a common perspective of Electoral College defenders, articulated most clearly in this National Affairs op-ed by historian Allen Guelzo:

A direct, national popular vote would incentivize campaigns to focus almost exclusively on densely populated urban areas; Clinton's popular-vote edge in 2016 arose from Democratic voting in just two places — Los Angeles and Chicago. Without the need to win the electoral votes of Ohio, Florida, and Pennsylvania, few candidates would bother to campaign there.

By forcing presidential candidates to win individual states rather than just individual voters, the Electoral College incentivizes them to campaign in smaller states where fewer people reside. The current system, therefore, is a crucial guardrail to make sure rural America doesn’t get completely ignored by the political class.

I have to confess something here: I am actually pretty sympathetic to the sentiment at the core of this argument. When conservatives make the case that getting rid of the Electoral College would lead to a deficit of attention to rural America, it’s often followed by a kneejerk response from urban progressives; something along the lines of “God forbid candidates campaign where people actually live!” Over time, I’ve come around to the position that this rebuttal misses the mark in a couple of ways, and comes across as pretty condescending to Americans who live in less dense areas. We’re a big country. And in a multicultural, geographically dispersed democracy, candidates should at least try to speak for all kinds of people, not just urbanites. Issues with unique impacts on rural America really do need attention—even disproportionate attention—because they are more likely to fall through the cracks in our nationalized media, urban-centric culture and globalized economy. New York Times diner interviews notwithstanding, it can be a struggle to actually hear the average rural, working-class voice.

But the main problem with the progressive “big cities are where all the people are” rebuttal is that it grants the underlying premise of Electoral College proponents’ argument: that if we transitioned to a national popular vote system, presidential candidates would only pay attention to and campaign in densely-populated urban areas. But the unfortunate truth for Electoral College defenders is that this prediction isn’t just wrong; it’s mathematically preposterous. The reality is that for any presidential candidate, a big-city-only campaign strategy would be electoral suicide.

Assume for a moment that we’ve done away with the Electoral College, and presidential elections are now decided by the national popular vote. In response, a candidate—Joe Biden, say—decides only to campaign in big cities in 2024 in order to rack up huge numbers of votes in the most population-dense parts of the country. Biden’s strategy is maximally successful: in this fantasy scenario, Biden wins over every single voter in each of the 100 most populated cities in the United States. We’re talking New York City, all the way down to Spokane, Washington. All told, this brilliant strategy would net Biden a whopping 26% of the nationwide vote. Nabbing the top 200 cities would get him all the way to… 33%. In this situation, Biden doesn’t cross the 50% threshold until he wins every single vote in every single one of the 671 biggest cities in America; and at this point we’re including massive metropolises like Pflugerville, Texas (population 48,000).

An urban-only campaign strategy clearly isn’t gonna get the job done in a country like ours. In a world without the Electoral College, Joe Biden still needs all of his rural and suburban supporters, and Donald Trump still needs all his urban supporters. No candidate could get away with only paying attention to one type of area alone, and big cities are simply not big enough to create some kind of permanent cabal that controls the popular vote; even if every voter in these cities pulled the lever for the same candidate, which they never have and never will.

Millions of voters are left behind completely

I’ve saved the most egregious violation of place representation perpetrated by the Electoral College for last: the fact that the votes of tens of millions of Americans are rendered completely irrelevant by it, simply by virtue of where they happen to live. This is because all but two states allocate their electoral votes on a winner-take-all basis, as New York Times columnist Jesse Wegman articulates here:

[Winner-take-all rules] erase all of the people in a state who didn’t vote for the person that wins the popular vote in their state. For example, there are fifty-five electoral votes in California and nearly six million people voted for Trump—which is more than most states’ populations. But all of those votes are treated as invisible because California will cast all fifty-five of its electoral votes for Joe Biden.

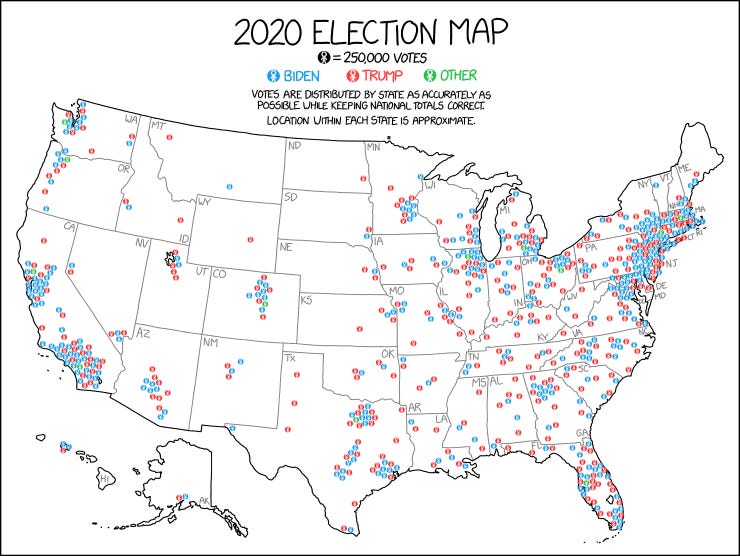

To make this travesty of place representation even clearer, let’s turn to XKCD’s beautifully-done 2020 election results map, which locates clusters of Trump and Biden voters based on where in each of the states the candidates perform strongest. And because every dot represents about 250,000 votes, it also accurately represents population density (for example, why California has a few dozen dots and Wyoming only has one).

What is this map telling us? Well, all those red clusters of Trump voters in California and New York are irrelevant. All those blue globs of Biden voters in Florida and Texas are irrelevant. Their votes simply don’t count because these states give all their electoral votes to the winner of their state, regardless of how much they win by.

To put an even finer point on how big a problem this is, here’s the caption on XKCD’s map, which is indeed accurate:

There are more Trump voters in California than Texas, more Biden voters in Texas than New York, more Trump voters in New York than Ohio, more Biden voters in Ohio than Massachusetts, more Trump voters in Massachusetts than Mississippi, and more Biden voters in Mississippi than Vermont.

The 2020 election would have turned out identically even if all the voters just described had stayed home. 38 million Republican votes in states Biden won, and 28 million Democratic votes in states Trump won—that’s 43% of all votes cast in 2020—were not just figuratively but literally meaningless.

So even if the Electoral College ensured state representation (it doesn’t), and even if getting rid of it would over-empower big cities (it wouldn’t), how could disenfranchising so many Americans just because of where they live possibly be worth the tradeoff?

Just about anything else would be better

The Electoral College doesn’t just fail to live up to its promise as a geographic equalizer; it is an astonishingly unfair and place-ignorant method of trying to ensure fair representation. It doesn’t preserve state-specific issues and representation. It doesn’t give rural America a consistent voice. And actual living, breathing voters who happen to live in certain places (in fact, most places) are completely ignored by the candidates, the media, the political class, and the vote count.

Meanwhile, in a presidential election determined by the national popular vote, a vote for Donald Trump in California would be every bit as valuable as a vote for Donald Trump in Arkansas. Both candidates would be incentivized not to post up in big cities and grub for votes for months on end. For sure they’d stop spending so much time in just a few swing states. They would go get votes wherever votes could be gotten.

A nationwide popular vote is, I’m sure, not a perfect solution. And I agree with the EC’s defenders that we need to design electoral institutions that take place representation into account. For example, I’d be in favor of a compromise that kept the EC, but forced states to allocate electoral votes proportionally, maybe with a bonus vote for winning the state as a whole.1

But as it’s currently designed, the Electoral College quite simply ain’t it. And we do ourselves and our fellow Americans no favors by pretending that it is.

This is essentially how Maine and Nebraska already do things; and both, by the way, received campaign visits from the candidates in 2020 despite their small size and non-closeness statewide.

That was very convincing. Do you have a sense for what it would take to actually initiate any kind of EC reform?

Finally, finally a summary on this complicated issue that makes sense.