What happened to all the Southern Democrats?

A century of racial backlash, party change, geographic sorting

In recent years, we’ve seen more and better attention being paid to the 1994 midterm elections as the inflection point for modern American politics, and the balance of power between the two parties. Readers with long memories may recall 1994 as the election when we were made all too aware of the existence of Newt Gingrich. In the political science world, the 1994 midterms are more commonly referred to as the “Republican Revolution,” in which the Republican Party claimed the majority of seats in the U.S. House of Representatives for the first time since 1955 (and only the third time since 1933).

But this is not the only major threshold Republicans crossed in this election cycle. The other was in located in a specific region of the country, where Republicans had been out of power for longer — and in more dramatic fashion — than they had in the nation as a whole. For the first time since the 1870s, the 1994 midterms helped Republicans also win a majority of U.S. House seats in the American South. It was here in the South that the Democratic Party had dominated for decades, and from which their domination of the Congress as a whole trickled down.

It’s difficult to imagine today, but it’s true. Between 1900 and 1963, Republicans almost never held more than a half dozen out of 120 or so Southern seats in Congress.

This is obviously not the case today. Republicans dominate the South (with some exceptions). So what happened to Southern Democrats? How, over the course of just a couple generations, could a party go from absolutely dominant to running for their political lives?

One possibly obvious explanation is that the complicated legacy of race in the South is central to understanding the Democrats’ political deflation in the region. The theory goes that by (reluctantly, far too late) taking up the banner of civil rights and Black empowerment in the 1960s and beyond, the Democratic Party alienated conservative white voters in the South, who have and continue to make up the vast majority of voters in most parts of the region.

A 2018 paper by Ilyana Kuziemko and Ebonya Washington looked into this very question, investigating the conventional wisdom that President Lyndon Johnson “lost the South” (despite himself being a Southerner) with his 1964 and 1965 push for the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts. Kuziemko and Washington analyze public opinion surveys in 1960, 1964, and 1968 to track how Americans were thinking about controversial race issues and the two major parties.

In 1960, both Southerners and Non-Southerners alike seemed torn about whether the Democratic or Republican Parties were more likely to push for racial integration in schools following the Brown v. Board Supreme Court decision in 1954. Basically, neither party had gained a reputation for supporting integration. By 1964, both Southerners and non-Southerners were many times more likely to agree that Democrats are the party of integration, while they’re more sure than ever that Republicans don’t support it.

Kuziemko and Washington mark the beginning of this shift as early as “the Spring of 1963, when Democratic President John F. Kennedy first proposed legislation barring discrimination in public accommodations. It was then that civil rights as a political issue not only became salient to the majority of Americans, but also clearly associated with the Democratic Party.” In other words, it became crystal clear throughout the 1960s which party you should support if you were in favor of more progressive race policies.

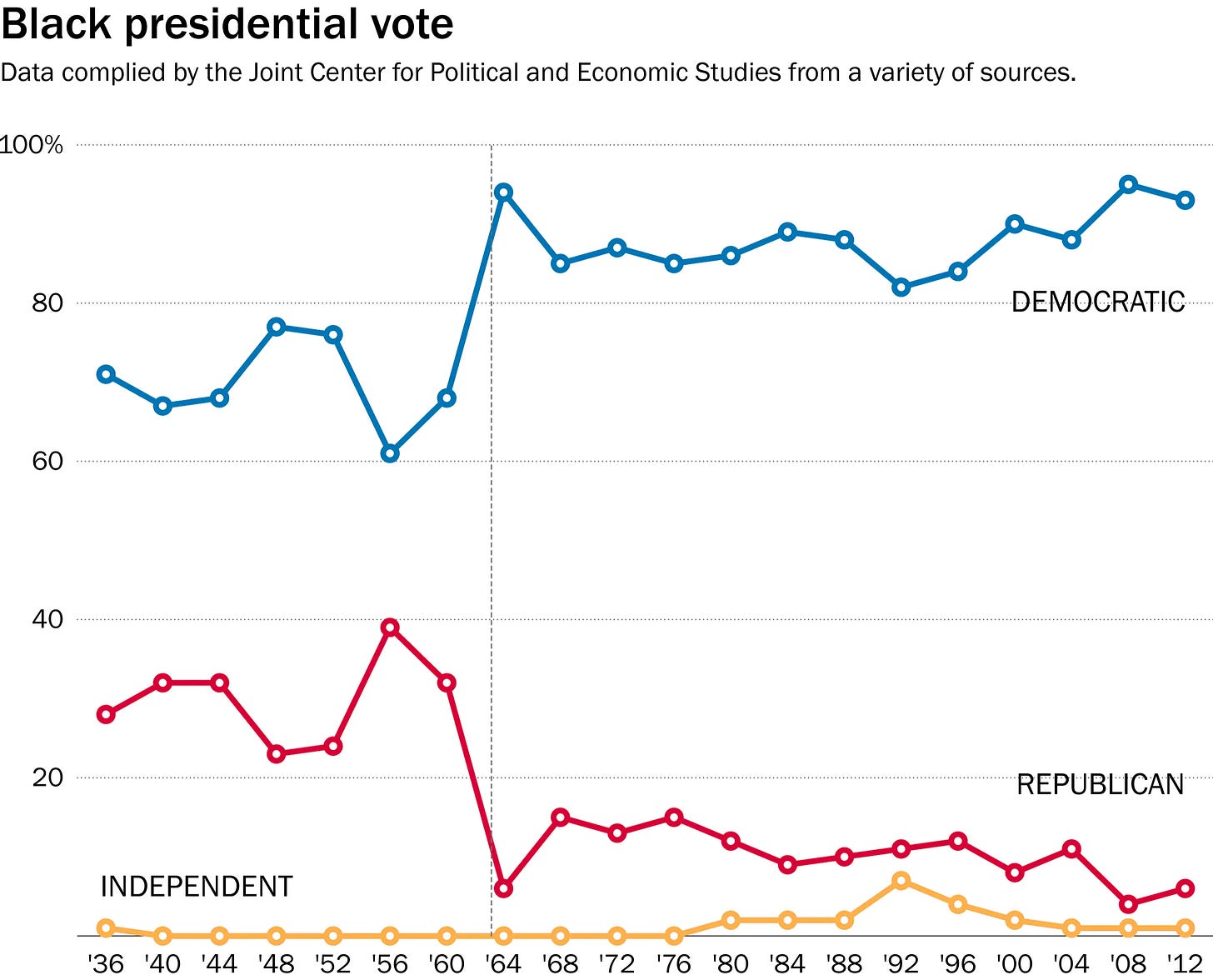

The chart below gives us one unmistakable result of this shift—a near-total abandonment of the Republican Party by Black voters starting with the 1964 presidential election. Since that election, Black voters have not given more than 19% of their vote to a Republican presidential candidate.

Another thing this chart tells us, however, is that Black Americans were already voting for Democratic presidential candidates by pretty decent margins even before the civil rights advances of the 1960s. Like most Americans, Blacks generally supported Franklin Roosevelt during the depression, and were particularly supportive of Harry Truman, who was generally more progressive than FDR (or any previous Democrat) on issues of racial discrimination. Truman’s rhetoric on race (which was pretty mild by today’s standards, and was not accompanied by major legislation) contributed to a walk-out by Southern Democrats at the 1948 Democratic Convention, and a third-party run by staunch segregationist Democrat Strom Thurmond of South Carolina.

We have other evidence, too, that the Southern realignment away from Democrats began before the Civil Rights era. Let’s look at just one more chart (one that I made, which is why it’s so attractive) that tracks White Democrats, Nonwhite Democrats, and all Republicans as proportions of Southern members of Congress over the past nearly 100 years.

At the dawn of the Great Depression, the South is represented in Congress almost uniformly by White Democrats. By 1964, that number is already down to about 75%. They’re still clearly dominant; but even before JFK or LBJ begin to push integration policies in earnest, Republicans are beginning to make gains. Something else is going on here.

That something is what political scientists call “partisan sorting,” and it happened in areas other than race policy. As FDR’s ambitious and (mostly) progressive New Deal began to take hold in the American imagination, we began to see a realignment of the two parties. In the times before the last century, progressive policymaking was not the domain of either major political party. Theodore Roosevelt (a Republican) was progressive; so too, in other ways, was his contemporary, Woodrow Wilson (a Democrat). By the 1940s and 1950s, however, it’s becoming clear that the Democrats are moving in a liberal direction, and are slowly but surely shedding their identity as the party of White hegemony in the South.

So yes, race is playing a major role here; but conservative vs. liberal ideology more generally is playing another, just as important role. In the decades after the New Deal, we see two parallel things happen: first, staunch conservatives in the South switch parties, away from the Democrats (this is what Sen. Strom Thurmond and others did); second, those folks’ children grown up not as Democrats, but as Goldwater or Reagan Republicans. In other words, the South was and remains conservative — not just on race, but on most issues. But in the interim, the party that embodied Southern conservatism completely switched in a matter of decades.

What the chart above also makes evident is the reality of Southern Black representation in Congress during Jim Crow—which is to say, there wasn’t any. Between 1900 and 1972 — and no, this is not a typo — there are exactly *zero* Black Americans elected to Congress from the South. Not a single one, for 72 years. This despite the fact that Blacks consistently made up between a fifth and a quarter of the Southern population during this time (and still do). This despite the 13th (1865), 14th (1868), and 15th (1870) Amendments to the Constitution, which were designed to grant equal political opportunity to newly-freed Black America.

And so although we have some helpful clues about the Democrats’ general decline in the South, we know that the bulk of their remaining support in the region comes primarily from Black voters. If you need more evidence to convince you of this, take a look at the super old map below, which shows the distribution of the enslaved population in the South as of the 1860 census; darker areas = higher concentrations of the enslaved.

What we see are major pockets of enslaved populations working plantations in a couple of distinct places: namely, the north-south boundaries around the Mississippi River straddling Louisiana and Arkansas to the west, and Mississippi to the east1; and in one pretty much continuous line cutting like a sharp plantation scythe from Chesapeake Bay-area Maryland, across central and eastern Virginia, curving down through the Carolinas (including coastal SC), and right through the middle of the deep South states. This is an area of the country traditionally known as the “Black Belt” — where plantations worked by enslaved Americans thrived in their heyday.

Now, let’s turn to the South and their counties’ voting patterns in 2020. Darker red areas are more supportive of Trump; Darker blue areas are more supportive of Biden. Notice anything? Any areas stand out?

More than a century and a half have passed since the first map was created, and yet here we are at the second. This is a kind of correlation that, as scientists, we can’t chalk up to random chance.

The explanation is simple, of course: Black Southerners support Democrats in such high numbers that the areas where they live pop off the page as the only truly “blue” parts of the South. But in doing so, these similarities reveal some frightening deficiencies of the effort to improve race relations over the past two centuries.

The reason these two maps are nearly identical is likely because:

Black Southerners largely only see one party (Democrats) as working in their interest

White Southerners largely only see one party (Republicans) as working in their interest

Black Southerners appear to be almost completely immobile from a geographic and socioeconomic perspective for the past 160 years

After all the change we’ve been through since the Civil War—in party views, in ideologies, in race relations, in our laws, and in generational growth—we are, in many ways, right back where we started. Racially divided, and partisan to the bone. The sick legacy of slavery, of rural plantation life, and a of long, lingering history of racial injustice have kept the Black Belt intact; it’s just that now, it overwhelmingly supports Democrats, instead of the “party of Lincoln.”

This is an area commonly referred to as the Mississippi Delta, where blues was born.

Really good work here. A few thoughts:

1. The spike in Eisenhower's share of the black vote in '56 I think was driven in part by Nixon pushing Ike toward at least some level of support for civil rights legislation (and eventually enforcing Brown). I also wonder what the educational split is--almost all the prominent civil rights leaders (Jackie Robinson, MLK, Sr. and Jr., Ralph Abernathy, etc.) supported Eisenhower. Then JFK's call to Mrs. King in 1960 changed everything.

2. The first campaign I remember was 1992, when it wasn't just Clinton winning most of the South, but both Senators were Democrats in AL, LA, TN, AR, and GA, all of whom were to the right of Doug Jones, to say nothing of Raphael Warnock or Jon Ossoff. Hell, even Gore was just four years removed from running for President as a pro-Hyde Amendment, pro-school prayer Democrat, conservative enough to get Rick Perry's endorsement. So like you said, a lot of this is overdue sorting into parties that actually align with values.

3. I wonder if the uptick in Black support for Trump in 2020 was the incumbency effect or the start of some greater shift away from Democrats. They've moved so sharply to the left on social issues, and survey data don't (sic) lie--after white evangelicals, Black Christians are the most socially conservative group. We won't know until November at least, but the Democrats have no margin for error to begin with given their coalition of Asian-Americans, over-educated white liberals (e.g., yours truly), and Black moderates.

This was very informative (and sobering!) ..and the chart you made IS attractive! I am actually printing out the maps in color and will have them for my students to discuss this morning!