Separating fact from fiction on redistricting

Time to bust some myths about the most misunderstood process in American politics

Hi folks! If you like my newsletter, and haven’t done so already, I really hope you’ll consider subscribing. It’s totally free, and comes out just once a week, straight to your inbox.

If you do already subscribe, it would mean a lot to me if you’d forward it to somebody who you think might enjoy it. Thanks, and enjoy today’s post!

A lot of people get a lot of things wrong about politics. But as somebody who studies Congress, I tend to overfocus on what people get wrong about the legislative branch. And more than just about any other topic, I think the redistricting process is prone to the most grievous misunderstandings—about what it is, how it works, and what could be better about it. It’s a very important process to me personally, since in a lot of ways it’s the ultimate synthesis of place and politics, and an embodiment of the idea that our elected leaders represent (or are supposed to represent) specific places, and not their political parties.

It’s also really important to me that people understand it. So today, I’m gonna run through a few of my (least) favorite myths about redistricting and correct the record as best I can. Let’s do this!

Myth #1: Gerrymandering and redistricting are the same thing.

As long as we’re stuck with congressional districts, we should probably get some terminology straight first, particularly on three main processes that people tend to conflate into one.

First, we need to make sure that states are getting their fair share of congressional districts, in proportion with the size of their population. We do this via the reapportionment process, which happens every ten years after we conduct the decennial Census and count everybody in the country.

Why do we do this? Because between 2010 and 2020, populations changed a lot between states, according to the Census counts: for example, Texas, Colorado, and Florida all gained in population, and thus need more representation than they did before; whereas Pennsylvania, Ohio, and New York all gained less or remained stagnant (Illinois actually shrunk by a few thousand residents), and so they don’t need as much. It’s not a perfect process, but it helps ensure that, unlike in the Senate, our representation in the House remains proportional to population so that everyone’s vote counts roughly the same.

Once reapportionment happens, we need to either make some room for new districts in states that gain seats, or merge some districts together for states that lost them; and even if we didn’t need to do that, plenty of people migrate within states, and we need to account for all of this by redrawing some lines. This is what we mean by redistricting: the changing of district boundaries to reflect population changes within the state, and whatever changes were wrought by reapportionment.

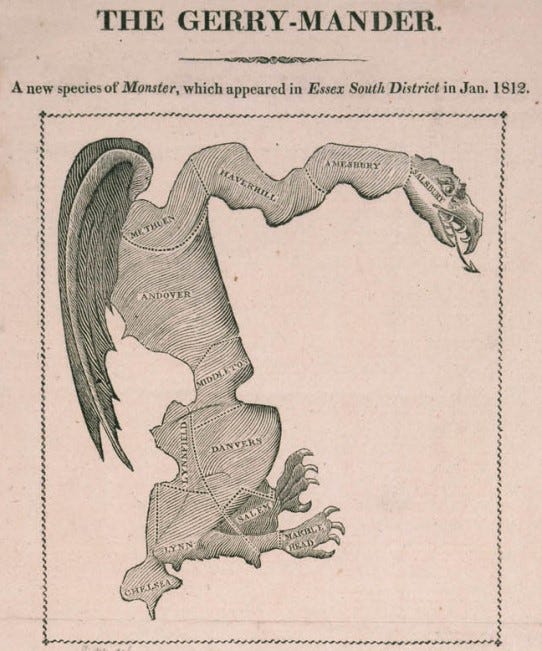

As we know, though, not all redistricting is created equal. The redistricting process is often used to favor the representation of one particular group or set of groups; this is what we have come to know as the boogeyman of gerrymandering. It’s origin is in the early republic, which found then-Massachusetts governor Elbridge Gerry signing a bill that created State Senate boundaries that purposely maximized the number of seats won by his party, the Democratic-Republicans. One of the districts resembled a mythological salamander (see below), hence the “gerry-mander.”

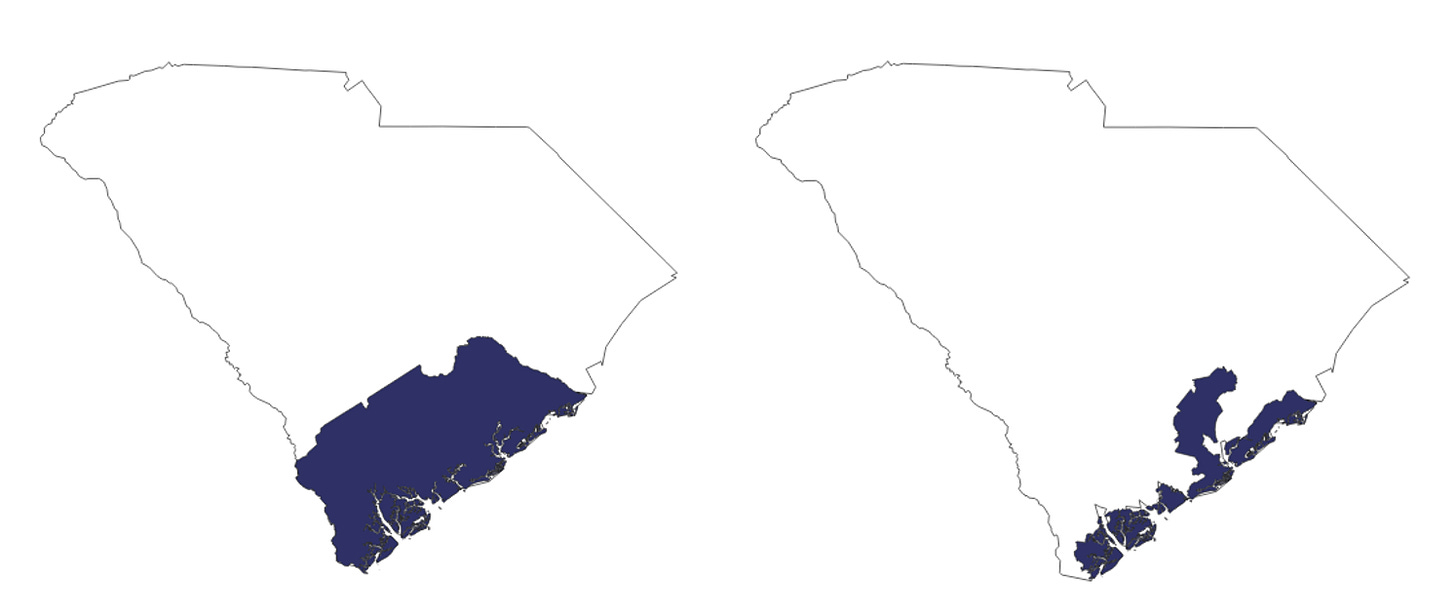

Today, gerrymanders are typically used in just this kind of fashion—to maximize the number of seats for one political party over another in a way that can really skew partisan representation in Congress. In 2021, for example, Republicans in South Carolina drew districts that handed their party six out of the delegation’s seven seats in Congress, despite the party’s winning only 56% of the vote in 2020’s presidential election. Democrats in Illinois, meanwhile, won 59% of the presidential vote in 2020; but after the 2022 midterm elections, they occupy 82% of the state’s congressional delegation, or 14 out of 17 seats, thanks to the heavily Democratic state legislature’s redistricting. The Supreme Court has ruled that this kind of gerrymandering is permissible, or at least that it’s not within the power of federal courts to get rid of it.

The other common form of gerrymandering is racial gerrymandering, which is done to minimize the voting impact of racial minorities. This practice is not permitted by law thanks to the Voting Rights Act of 1963 and subsequent Supreme Court decisions.

Myth #2: Congressional districts stay the same over time.

This one seems obvious, since any grasp of any of the definitions I just talked about would let us know that nearly all congressional districts1 change their boundaries at least once every ten years.

But the news media’s stubborn refusal to internalize this fact in their reporting has become the bane of my existence, and they make the same mistake every time. “A Republican has not represented the 5th Congressional District since 2006,” declares one Associated Press article from last year, even though thousands of the district’s residents have been born, died, or moved in or out during that time, making the district and its voters completely different even if its boundaries were the same.

But of course, the boundaries aren’t the same—they rarely are. “No Democrat", asserts another from the Greenville (SC) News in 2018, “has held [South Carolina’s 1st congressional district]” since 1980,” even though the 1st encompassed an almost totally different part of the state back then. The geographic boundaries of districts almost necessarily change every ten years (at least), which means the district being referenced here has different counties, residential areas, and of course people as it did back in 1980, four redistricting cycles ago. So comparing today’s district to its 1980 counterpart is nonsensical.

An article on Tennessee’s 2nd congressional district from back in 2017 really takes this error to new heights: the district, reporter Tyler Whetstone writes, “hasn’t been held by a Democrat since before the Civil War in 1855, so it’s been a while.” Yes, Tyler, it sure has! During this gap of time, many generations of Tennesseans have lived and died; and the district changed in size, shape, and where it is on the map. But even if neither of these things was true, the two major parties are so dramatically different today from what they were in the 1850s that it still makes this piece of information useless at best and deeply misleading at worst. Back then, the Democrats were generally pretty conservative, agrarian, pro-slavery, and completely dominant in the South. The Republican Party barely existed, and had not yet even fielded a presidential candidate. So why on earth are we using the parties as a comparison point?

The thing is, I actually do understand why journalists use these figures: they want to get across in a shocking way how unexpected one party’s victory was or might be, and this turn of phrase is simple a way to do it. Maybe they want clicks and shock value; maybe, to be more charitable, they want to properly inform the reader how lopsided a district is. But there are dozens of other ways to get that point across without recycling what amounts to almost totally irrelevant information. It’s like trying to communicate the value of a fraction by putting the birthday cake emoji where the denominator should be (🎂).

You can probably tell, but to say this is a “pet peeve” of mine is the understatement of the year. Even though I realize it’s not technically a big deal and that nobody cares about this but me, the persistence of these errors has kindled a simmering grudge that I simply can’t let go. The clearest way I can explain this is that I feel like the Ryan Gosling character in that amazing “Papyrus” SNL sketch from a few years ago.

Myth #3: Gerrymandering is why Democrats can’t hold onto the House of Representatives.

This is one I’ve covered more extensively in other spaces, including an article I wrote a few months ago in The Conversation. I won’t rehash the whole argument here, except to say that I’ve gotten used to hearing Democrats—and only Democrats, it seems like—criticize gerrymandering as the root of all evil, the reason Republican politicians won’t compromise, and the reason Republicans keep winning the House. The argument, in essence, is that if it weren’t for gerrymandering, Democrats would control the House of Representatives more often and win more seats more regularly. But for the most part, it just ain’t so.

In 2022, Republicans won 51% of House seats, and 51% of the nationwide popular vote for Congress. These numbers also aligned perfectly in 2020, and in 2018. In fact, the 2012 U.S. House elections were the only ones in modern history where a party won the national popular vote in the House, but didn’t control the chamber. And if anything, Democrats were much bigger beneficiaries of redistricting up through the mid-1990s than Republicans were during the Obama years, as we can see in the chart below that I made in collaboration with The Conversation.

Gerrymandering is a problem, but it’s not the type of problem Democrats tend to think it is. For one thing, it’s a bipartisan vice. Both parties do plenty of gerrymandering; Republicans in states like South Carolina and Wisconsin are masters of this dark art, but so are Illinois and Maryland Democrats.

For another, Democrats are much more consistently disadvantaged by a process called geographic sorting. Over the past half-century, voters in urban areas have increasingly affiliated with the Democratic Party. These areas have a lot of voters, which is great for Democrats, and is where the bulk of their congressional seats come from. But these areas are also really small geographically. This “clustering” of Democratic votes in big cities makes it more difficult to draw district lines that get Democrats the most possible seats in Congress.

Because Democrats live in denser, more tightly packed places, they can’t distribute their votes as efficiently among geographic districts throughout a state. So when they win in big cities, they win big—which is great, except that also means they’re “wasting” more votes than their Republican counterparts. That this is a problem for Democrats is undeniable—but it’s not a problem gerrymandering caused.

Myth #4: The solutions for partisan gerrymandering are simple.

All that said, I’ll be the first to admit that the redistricting process is very far from perfect. Gerrymandering really is not a good thing even if it’s not exclusively bad for Democrats. For one thing, it’s bad for regular Americans. My own research shows that changing district lines can disorient voters and reduce turnout. It can also cut into voters’ sense that their votes make a difference in the same way the Electoral College does: Democrats from South Carolina and Republicans from Illinois, would, I believe, feel better represented if they could see congressional delegations that more accurately reflect their state’s electorate.

So what can we do about this? “Get rid of gerrymandering!”, reformers shout. Okay, great—but how? Reforming the redistricting process is frustratingly complex. Dozens of criteria go into line-drawing decisions, and policymakers have to make hard choices about what to prioritize, and what to deprioritize. Should we try to make districts as evenly-split between the parties as possible to stimulate competition? Should we try to create as many majority-minority districts (that is, districts where racial minorities can predominate) as possible? Should we try to hold together county and city lines at all costs, rather than cut through natural communities? As you might imagine, these priorities—all of which are important—don’t always play nicely together.

A more comprehensive reform would be to get rid of congressional districts altogether. Instead, let’s vote nationwide for parties instead of people, and fill seats in Congress according to how well the parties do nationwide. This might provide good party representation, but I have concerns about such a total de-placing of American political representation. Different places really do have different needs, and this reform—commonly referred to as proportional representation—could zero those differences out and leave vulnerable American places behind. And at any rate, it’s such a monumental change that it’s impossible to imagine Congress or any legislative body endorsing it anytime soon.

Instead, we could focus on the entities that conduct the redistricting process to begin with. At this time, 37 out of 50 states entrust this process to politicians themselves—specifically, their state legislatures. Letting politicians draw their own district lines, and the lines for congressional districts, is obviously problematic, and probably a good place to start if we want to make redistricting fairer. In Idaho, we use an independent, bipartisan commission that seems to do a pretty reasonable job of drawing lines using a bunch of important criteria, and without a ton of drama.

Commissions are not perfect, nor do they come close to solving all of the issues and complexities that come with redistricting. One recent study from Robin Best and co-authors found that although commissions “do seem to generate congressional district maps that contain less partisan bias than those produced by state legislatures”, they don’t always do so. But even when they fail, commissions can take (some of) the politics out of the process and remove the impression that legislators are pulling one over on their own voters; that seems like a fair place to start.

Except for small-population states with single “at-large” congressional districts like Vermont, Alaska, and Wyoming, for whom their district boundaries are exactly the same as their state boundaries, and therefore don’t change.

I remember being tracted by a group collecting signatures for a redistricting policy proposal of some kind (don't know the right terminology) in Utah--I think it was to have a bipartisan committee. That was like 10 years ago, not sure how it is in Utah now.

Also pooling all votes in the nation is sort of a mind boggling idea given how vast the US is--it seems like it would make more sense in a small European country. But I've never really thought about that possiblity before, actually.