I may have gotten lost on a Scottish mountainside

My afternoon meandering across the moorlands, and how I set my sights on a way out

Sinking knee-deep into a countryside bog was not on the detailed itinerary my wife dutifully maintained for our two-week vacation across Scotland; but there I was nonetheless. It was the end result of a kind of desperate careening I was engaged in on my way down a hill called Ben1 Tianavaig (roughly pronounced “shin-uh-vig”) on the outer edges of Portree, on the Isle of Skye. I had lost balance but gained considerable speed at the same time, which, it turns out, is a poor combination. Once at the bottom, my foot did not strike solid ground so much as it sank several feet into a wet, muddy bog that was so thick with undergrowth that I couldn’t see it on my descent.

I stood there, pretty fully submersed in god-only-knows-what; I was tired, at the tail end of an arduous hike; and if there had ever been an actual trail on the way down, I had misplaced it (or perhaps it had misplaced me) long ago. Only my right leg had sunk into this mud pit, but both legs were significantly worse for wear after prolonged contact with plant growth.

Thankfully, I had a way out of my predicament, even it wasn’t the way out I had planned. And so — even while standing awkwardly in a bog waiting for some subterranean cousin of the Loch Ness Monster to suck me underground for all eternity — I found it in me to laugh instead of curse. Okay, I probably cursed, too, but then I laughed at my predicament, yanked my leg out of the ground to assess the damage, and went on my still reasonably merry way.

My hike wasn’t supposed to be this way, and for awhile, it wasn’t. At only around 1,300 feet, Ben Tianavaig is by no means a major climb by the standards of the Scottish Highlands. It doesn’t even qualify as a “Munro”, which (I have learned on this trip) is a Scottish mountain of over 3,000 feet in elevation. Just days before my hike, a woman sitting near us at lunch boasted that she had “bagged seven Munros” in this week alone.2

Tianavaig is instead what author and surveyor Alan Dawson termed a “Marylin” (a punny companion to “Munro”), which more or less means a relatively small hill. With such an unimposing description, it was no wonder our Airbnb suggested ascending it as a worthwhile outdoor activity during our stay. My wife and I decided to give it a shot. The directions our hosts included in our itinerary claimed that a trail to Tianavaig could be found just a short walk from the house, on the north side of the mountain. These instructions were suspiciously short: merely to “enter the field” through a farm gate across the street, then “meander across the moorland until you reach the summit.”

Meander we did, but no trail did we find. After some significant squishing in boglands, followed by a run-in with a group of cows that looked ready to throttle us should we dare to “meander” too close to them, we gave up and turned back.

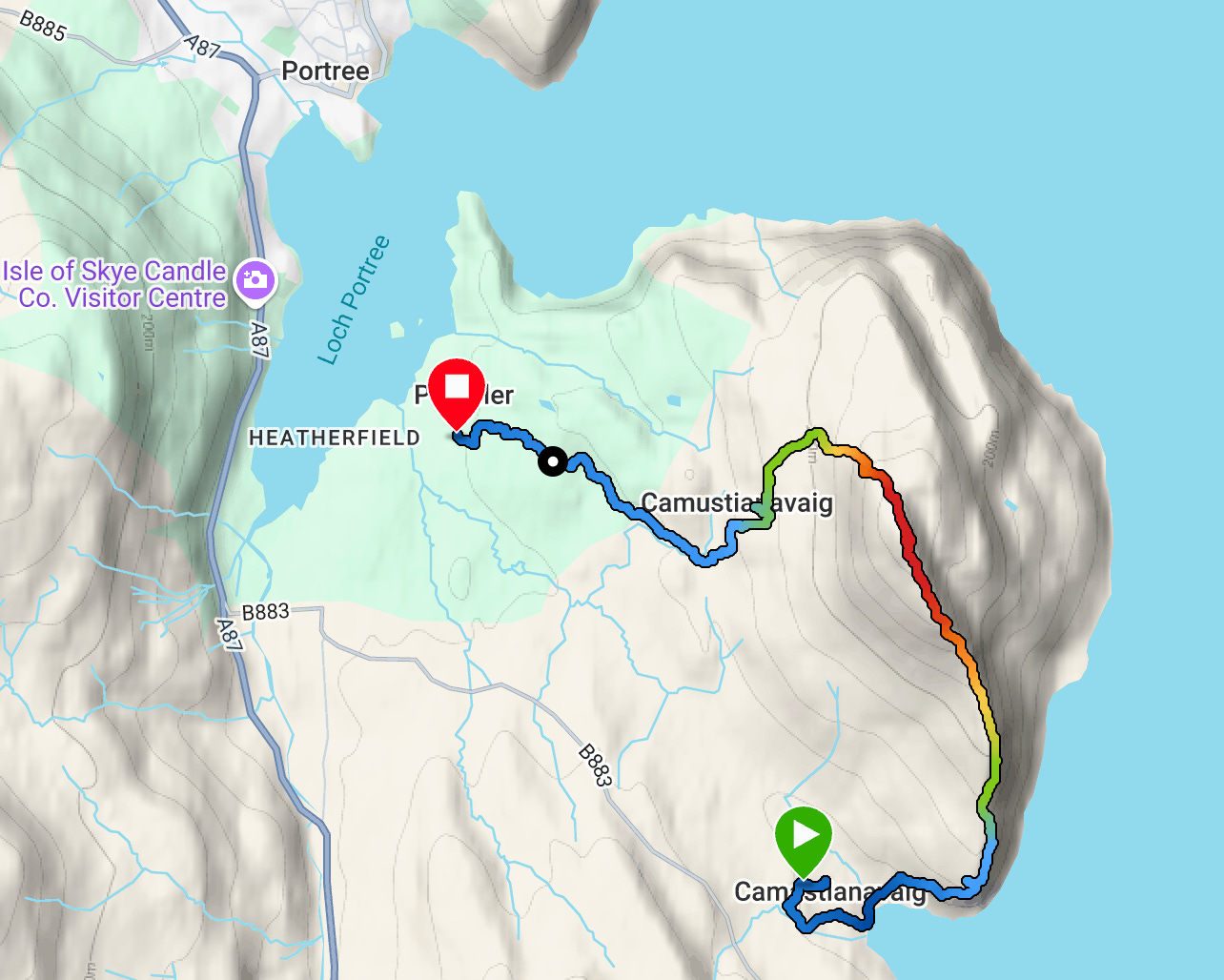

A reasonable person — one capable of internalizing the concept of relaxing while on vacation — would have decided to do something else with their day after that. By now, you know that I’m no such person. Instead, I used what the hosts called the “alternate route” up the mountain. This was, in fact, the correct, established route on the south side of the mountain that can actually be found on Google Maps and AllTrails. It began with a clear starting point; an actual, well-maintained path; clearly-marked signage; and GPS coordinates on my Garmin Watch for good measure. It was a stupefyingly beautiful hike, even though it was (for a mere “Marylin”, anyway) quite steep and difficult for an infrequent mountaineer like me. The views, as you can see below, were characteristically stunning.

I was feeling pretty proud of myself upon reaching Tianavaig’s summit, and possibly a little reckless. If I went back down the way I came, I would know precisely where I was going, and where I’d end up. I wouldn’t be able to see the trailhead at the bottom, but I had a clear path all the way down (the one I’d just come up). Even so, it would be more inconvenient to get back (that is, somebody would have to come pick me up to drive me back to the house). On the other hand, after turning 180 degrees in the other direction, I could actually see with my own eyes our Airbnb, and right near it a tall electrical tower that could be leveraged to find my way back, on foot.

When my wife and I tried to find the path this morning, it was based on (I presumed) shoddy directions from our hosts; why instead, I reasoned, shouldn’t I be able to find the path from the top of the mountain down, where I’d have a clear view of everything? Not only would nobody need to bother coming to pick me up, but I would also return as a conquering hero, having discovered (like an interloping Scottish Magellan) the intended path, thus clearing the way for my fellow travelers to use it without issue.

And so a decision was made, using a rubric that can only be accurately described as “Fuck It.” I began bounding, with no clear path but a great deal of hubris, down the north side of Ben Tianavaig towards home.

Now seems like a good time for a few words about humility — in particular, the humbling power of nature on the human ego.

As I’ve written about here before, there’s no doubt that humans have (to borrow a phrase from the Brits) made a right pig’s ear of our earthly inheritance. We’ve screwed things up royally; yet we also know that in the end, when our species has come and gone, the natural world — however damaged — will likely still be here, grow again, and messily replace what we’ve destroyed. Through every ice age, stone age, and dino-extincting meteor, mother nature and her magical process remain the undefeated champs.

This is a lesson I would have done well to remember the other day. It’s a lesson put to elegant words by Scottish poet Kathleen Jamie, who from 2021-2024 was Scotland’s Makar (their version of the “poet laureate” position we have in the States). Here’s a portion of her poem “Moor”, set in the same Scottish moorlands in which I was heedlessly meandering the other day:

What do we sense on the moor but ghost folk,

ghost deer, even ghost wolf. The path itself is a

phantom, almost erased in ling and yellow tormentil:

flowers of this summer and this summer only,

even as they flourish they’re passing into memory,

already bequeathing themselves —The moor in summer dreams itself out of all

previous summers. Bog-cotton, the green fritillary,

the fly-catching sundew … likewise the larksong,

all iterated as though for the first time.It is their first time! And every time before.

Even more so than the average resident of Portree, the Isle of Skye, or even of Scotland as a whole, I was a true interloper on the land atop and surrounding Ben Tianavaig. Unlike the flora, the fauna, and the “bog-cotton” (of which there was plenty on the way down to trip me up), it really was my first time here, and I was not acting like it. The mountainside of Ben Tianavaig makes itself anew each year, “as though for the first time.” But of course, it’s not for the first time. You can set a watch — or rather, a calendar — by the unmaking and re-making of landscapes that takes place each year. In the scheme of things, a passing summer is just a mountain’s single out-breath, following an in-breath of winter, repeated for millennia before some tourist arrives to climb it, and for millennia after he leaves.

My own path down the mountain, as Kathleen Jamie puts it, turned out to be “a phantom, almost erased.” It was a ghost path to go along with the “ghost folk” and “ghost deer.” Coincidentally, I did see actual, non-ghost deer on my way down the mountain, in addition to actual cows and sheep; but no actual folk. That’s because there was, in the end, no reasonable path for a human to trod down the north side of Ben Tianavaig.

There was tall grass, uneven rocks, and patches of bog, none of which pointed towards a trail of any kind. So it was that I ended up in my humbled state, knee-deep in the moorlands, scratched up but (technically) still standing.

Fortunately, the story didn’t end quite so tragically, with me still stuck days later, at the mercy of the elements, as well as a flock of imposing sheep who clearly were better-equipped for this landscape than I was. “Man is promptly humbled by nature” is the oldest lesson in the book, but I had one more to learn before I pulled my leg (and my dignity) out from the mud.

It’s true that I was “lost” in one sense of the word: I did not have a clear path, and AllTrails had stopped being helpful just minutes after I left the summit. But what I did have, for the entirety of my farcical tumble down the hill, was a high-flying power station tower located just a short walk away from the Airbnb.

Since the beginning of this year, I’ve hurtled headfirst into my first real, lasting yoga practice. It’s here that I’ve learned about the concept of establishing a drishti, which in yoga stands for a kind of focal point: an object in your line of vision that you can keep your eyes focused on during balancing asanas (poses) like Tree, Dancer, or Eagle. These are poses usually undertaken on one foot; as a result, the body has less information about where it’s situated in space. By training your eyes on a drishti, you’re using a makeshift compass to orient yourself towards a point at the front of the room, and providing your body a pathway towards striking the pose. No matter where you are on your way to the pose, or how far you’ve strayed from the “correct” version of it, your drishti is available to guide you back, however “inefficiently.”

Such was the service this tall tower, a notably non-natural landmark, was providing to me. No matter which smaller hill I got lost behind, or which flock of sheep was savagely judging me, I had my central focal point of the tower; and thus, a way back home.

In yoga, we’re constantly reminded that establishing a drishti does not foreclose the possibility of losing balance or falling over during the duration of the pose. Ships with anchors still sway in the water, and bodies stabilized with focal points still shift on their fallible feet. What a drishti does is make it easier to get back up, re-establish your presence, and return to where you’ve been. You lose the path, you return; you get distracted by a cute baby sheep, you return; you fall into a disgusting bog, you return.

No yoga pose nor hike I’ve ever undertaken has been perfectly executed without error, nor done in a flawlessly straight line, nor walked without a tumble along the way. For most of us, flawless execution is the farthest thing from the goal of any yoga practice. Each pose is a winding path with unexpected turns and obstacles to move around, and each person who does the pose gets there a different way. If the map of my journey captured by my watch is in any way accurate, my trip down Ben Tianavaig was no exception.

I won’t pretend I was enveloped in a perfect spirit of zen during my rapid, ungainly descent. I was properly annoyed by my own presumption that this would be a cakewalk. But I did manage enough presence of mind to be able to find a serviceable path home; to locate a good bit of amusement in my predicament; and even, thanks to my tower-like drishti, set my sights on a hint of gratitude for the obstacles along the way.

I’ll leave you with one more short poem for the road, however weedy and winding it may be.

“A Walk”

by Rainer Maria Rilke

My eyes already touch the sunny hill. going far beyond the road I have begun, So we are grasped by what we cannot grasp; it has an inner light, even from a distance- and changes us, even if we do not reach it, into something else, which, hardly sensing it, we already are; a gesture waves us on answering our own wave… but what we feel is the wind in our faces.

Translated by Robert Bly

Generally, Scots use “Ben” the same way we might use “Mount” (e.g. Mount Rainier), except for smaller hills.

Had we not already been armed with our topographical facts, this could have meant something very different and far more exciting.