Breaking our great barriers, and building them back

The miracle of Notre Dame, the tragedy of the Great Barrier Reef, and what human hands do in between

“A Pope from Chicago” sounds like the beginning of an irreverent Billy Collins poem, or even a potentially offensive joke. But in fact, it’s the new reality of the Roman Catholic church, whose papal conclave selected Cardinal Robert Prevost (now Pope Leo XIV), an American who was born and raised in and around the Windy City, as the its new pontiff last week.

The selection of a new Pope, and the potential for change that follows, provide a really interesting opportunity for spiritual reflection, and not just for Catholics. In this case, the selection of this unlikely pope — who betting markets had no clue was in the running until his name was announced — gives all of us a chance to consider some other unlikely paths to renewal, and even to holiness (if that’s your thing).

For two such paths — one we’ve taken against all odds, and one I pray we’ll take in the years ahead — let’s get an assist from maybe our best living American writer (to go along with our American pope): the novelist, essayist, and, yes, the poet, Barbara Kingsolver.

“Great Barrier”

by Barbara Kingsolver

The cathedral is burning. Absent flame or smoke, stained glass explodes in silence, fractal scales of angel damsel rainbow parrot. Charred beams of blackened coral lie in heaps on the sacred floor, white stones fallen from high places, spires collapsed crushing sainted turtle and gargoyle octopus. Something there is in my kind that cannot love a reef, a tundra, a plain stone breast of desert, ever quite enough. A tree perhaps, once recomposed as splendid furniture. A forest after the whole of it is planed to posts and beams and raised to a heaven of earnest construction in the name of Our Lady. All Paris stood on the bridges to watch her burning, believing a thing this old, this large and beautiful must be holy and cannot be lost. And coral temples older than Charlemagne suffocate unattended, bleach and bleed from the eye, the centered heart. Lord of leaves and fishes, lead me across this great divide. Teach me how to love the sacred places, not as one devotes to One who made me in his image and is bound to love me back. I mean as a body loves its microbial skin, the worm its nape of loam, all secret otherness forgiven. Love beyond anything I will ever make of it.

I am not Catholic, but I have the cultural markings of one. My native Rhode Island is, at least as of 2017, the most Catholic state in America (44% of adult Rhode Islanders, compared to 23% of all Americans). My parents were raised Catholic, and although my brothers and I were not, the schools we attended tended to be named after ordained saints. We knew our Jesuits, our Franciscans, and even our Augustinians (like our new pope). I also harbor tremendous quantities of personal guilt and self-doubt, but that could just be something else. More than anything, I feel a strong cultural affinity for Catholicism even though I wouldn’t call myself an adherent of the faith.

This “cultural Catholicism” might help explain why in 2012, during my first trip to Paris with two dear friends, I had only one visit on my list that couldn’t be ignored: Notre-Dame cathedral, or Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris, if you’re fancy. Notre-Dame was and is one of the most recognizable buildings in the world, and the centerpiece of Catholic life in Paris, and probably for all of Europe outside of Vatican City.

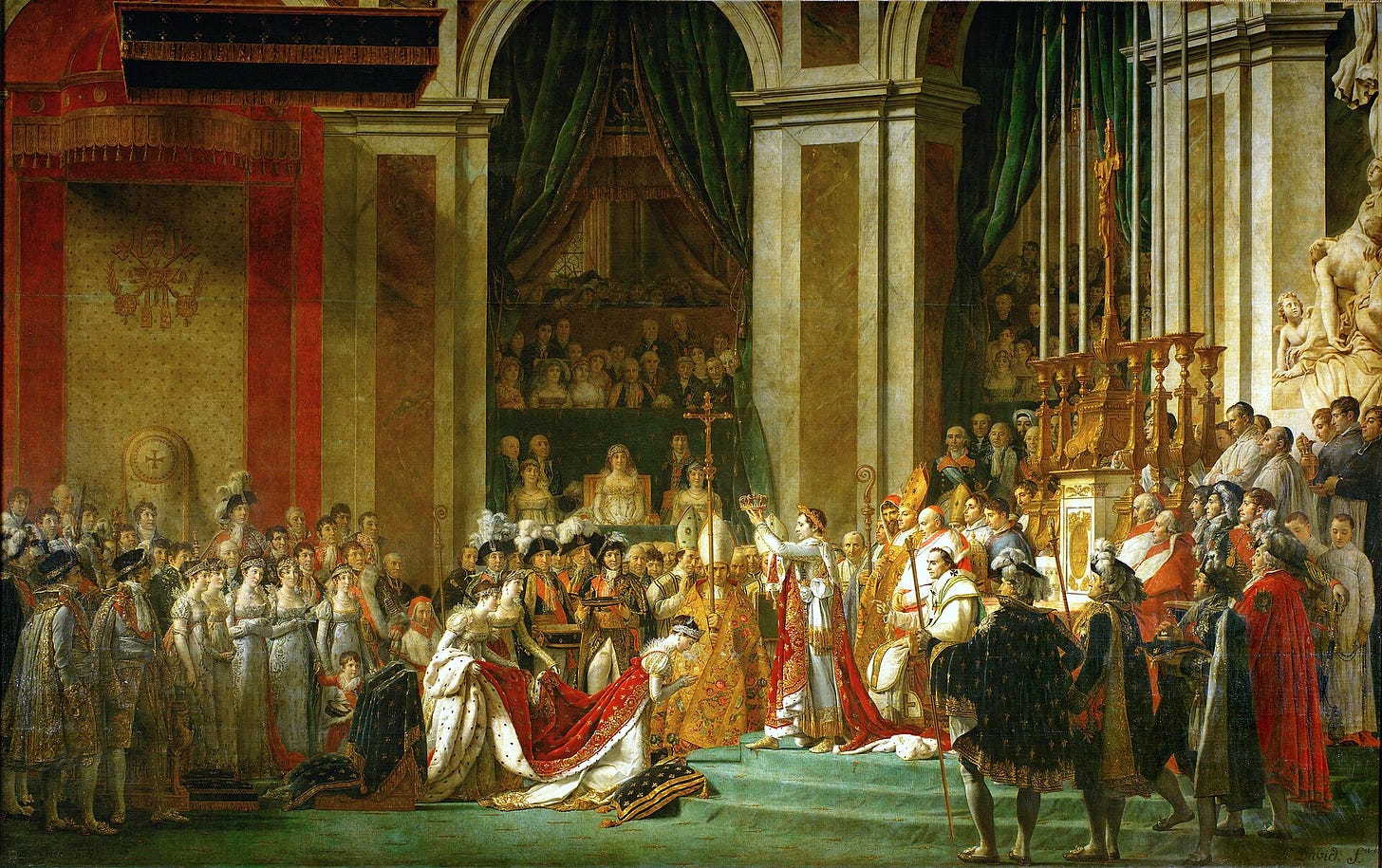

Centuries of popes, kings, queens, and dignitaries, along with millions of adoring Catholics, have passed through the halls of Notre-Dame. Mary Queen of Scots was was married there; Joan of Arc was beatified there as a saint; Napoleon Bonaparte was even crowned in Notre-Dame in 1804, as Pope Pius VII looked on approvingly at the right hand of the new emperor.

Even at that time, the cathedral was already nearly 600 years old. It began construction in 1163, which my math whiz readers could tell us is a staggering 862 years ago.

Many churches and cathedrals around the world are older, but possibly none is grander. As I walked through the near-silent cathedral back in 2012, I — again, a non-Catholic — was left breathless in ways I didn’t know were possible, bowled over by the sheer tonnage of history and faith embedded in the walls. The “stained glass”, as Kingsolver writes, “exploded in [its] silence.” I lit a candle, and probably didn’t exactly say a prayer; but I know that I marveled at the holiness of human achievement that surely even the most intransigent atheist would have to admit to upon seeing those “fractal scales/of angel damsel rainbow parrot” shining through the cathedral’s towering windows.

But as we know, it wasn’t to last. On April 15, 2019 (presumably the day Kingsolver began writing that poem) Notre-Dame burned. Responders were thankfully able to stop the conflagration before the entire cathedral burned to the ground, but the amount of damage done by the fire was significant and seemingly irreparable. I’m not ashamed to say that the potent combination of emotions I felt while walking through the cathedral just a few years earlier was replicated on that day on the other side of the ledger. There’s no other word for it: I was heartbroken, and I know I wasn’t alone.

But like any great poet and truth-teller, Kingsolver snaps her fingers in front of our faces as we clutch our pearls and watch a man-made structure fall to pieces. By around the same time Notre-Dame burned for the world to see, undoing centuries of work by generations of human hands, the world had also witnessed the near-total devastation of another great wonder of the world. And in this case, human hands are the ones to blame.

As the world’s largest living structure, and the only living structure visible from space, the Great Barrier Reef is the exact opposite of man-made. But the quick and methodical destruction of the Reef over the past century or so almost assuredly is. Much of the Reef’s 1,400 miles of living coral has died or been permanently damaged thanks to mass bleaching brought about by human-caused climate change. The destruction is so vast that Outside magazine published an obituary for the Reef (25 million BC - 2016). The damage is so raw, so clear, and so deep that Outside came to the conclusion that there’s no coming back:

In his 2008 book, A Reef in Time, J.E.N. Veron wrote that back then he might have ended his book about the reef with “a heartwarming bromide: ‘And now we can rest assured that future generations will treasure this great wilderness area for all time.’” But, he continued: “Today, as we are coming to grips with the influence that humans are having on the world’s environments, it will come as no surprise that I am unable to write anything remotely like that ending.”

I trust the science that says the Reef is in significant danger. But my hope is that Kingsolver’s inclusion of the Reef alongside the example of the Great 2019 Heartbreak of Notre-Dame is a kind of chance indicator, a serendipitous forecast that even in these bleakest of moments, things can change for the better. This is the hope I held on to and celebrated when I read just a few months ago that in December of 2024 — only five short years after it nearly burned to the ground — Notre-Dame re-opened in Paris after an “Astonishing Rebirth from the Ashes.”

The New York Times story by Michael Kimmelman that I’ve just linked to tells the full tale of Notre-Dame’s reconstruction, including the truly unbelievable pace with which it rose again into its full majesty. French President Emmanuel Macron’s promise to rebuild it in five years seemed, at the time, like a fool’s promise — or, even worse, a politician’s promise. And yet — even in the midst of a raging pandemic, an unpredictable global economy, and Lord only knows the political challenges — it happened.

But how? There are many technical explanations, and Kimmelman relates many of them in his story. But the explanation that follows seems most plausible to me:

“Each day we have 20 difficulties,” Philippe Jost, who headed the restoration task force, told me. “But it’s different when you work on a building that has a soul. Beauty makes everything easier.”

I can’t recall ever visiting a building site that seemed calmer, despite the pressure to finish on time, or one filled with quite the same quiet air of joy and certitude. When I quizzed one worker about what the job meant to her, she struggled to find words, then started to weep.

There remains something poetic and bittersweet about the miraculous rebuilding of a testament to man-made places while we continue to destroy natural places with those same hands. I don’t know how Barbara Kingsolver would feel or does feel about the sheer force of will that rebuilt Notre-Dame at such a stupefying pace. Perhaps she would applaud it. But perhaps also she would say (and a small part of me might agree) that every ounce of energy, manpower, and market power summoned to restore Notre-Dame to its former majesty should have been redirected, dollar for dollar, joule for joule, towards proving Outside magazine wrong by protecting, then restoring, the Great Barrier Reef.

That may be true. It may also be true that humanity has built up so much prosperity for itself that surely it can care for both its man-made treasures and its natural ones.

Because despite Outside’s proclamation, it’s also true that even the Great Barrier Reef itself can recover. Unlike Notre-Dame, it has natural processes for returning to its original grandeur, and could still do so. According to the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS), 2022 saw the highest levels of coral cover in the Reef in more than 30 years. It’s the faintest of indications that efforts to save the Reef from climate disaster might be having some effect. “There’s no question this is positive news,” said Konrad Hughen, a principal investigator on the Reef Solutions Initiative. “These data show reefs can recover rapidly from damage.”

They can — but they must be allowed to. Human effort was not just helpful, but necessary, to restore Notre-Dame to its former glory. In this case, though, human restraint is what’s called for, combined with active efforts to study, then reverse, the harm we’ve caused so far.

For humanity, it’s a lack of restraint that often stands as the biggest, greatest barrier of all to real, lasting environmental stewardship. Our new Chicago Pope (sorry if it’s blasphemous to call him that, but it’s with love) has said as much. He’s challenged world leaders — like his predecessor, Pope Francis did — to move "from words to action" on the environmental crisis.

Care for our wondrous, wise, and inscrutable natural world is the only way to make uniquely human achievements like Notre-Dame’s recovery even possible. And because I’m left with no other choice, I must continue to hope we can do both.

Amazing piece! I think I'll be using the save feature for pretty much the first time. :)