We three kings of Orient probably aren't

A brief Christmas poem to tide us over until next week

I’m pleased as punch to be finished with what has probably been my busiest semester of professor-ing yet (this was my eleventh thus far). The deadlines, the grading, and the election are done. I’m back in Rhode Island visiting family for the holidays, which is lovely, but which also means that this week’s post will be short and sweet to allow for maximum decompression, togetherness, and frequent trips to Dunkin’ Donuts. I also have grand plans for a special Christmas Eve post next week that needs more time to marinate. Suffice to say that if you’re a Harry Potter fanatic like me, you may wish to give it a look.

Until then, enjoy this brief and bewildered Christmas poem from the perspective of those wise guys who paid baby Jesus a visit:

“The Three Kings”

by Muriel Sparks

Where do we go from here? We left our country, Bore gifts, Followed a star. We were questioned. We answered. We reached our objective. We enjoyed the trip. Then we came back by a different way. And now the people are demonstrating in the streets. They say they don't need the Kings any more. They did very well in our absence. Everything was all right without us. They are out on the streets with placards: Wise Men? What's wise about them? There are plenty of Wise Men, And who needs them? -and so on. Perhaps they will be better off without us, But where do we go from here?

The last couple of weeks have been tough ones for authoritarian (or authoritarian-adjacent) leaders on the international scene—the wannabe “kings” of the modern, supposedly-developed world. Yoon Suk Yeol, the president of South Korea, was impeached in bipartisan fashion (imagine that) after he declared martial law and inspired a nationwide protest against him. Bashar al Assad, who ruled Syria for the last quarter century and seems to have used sarin gas against his own people, was finally run out of town and fled to Russia. Benjamin Netanyahu is on trial for corruption in Israel and continues to be a twerp.

These “three kings” are all various levels of bad news (just my opinion); but as far as our friends in today’s poem go… let’s just say, I feel for these guys. You try to do something nice, honor the Messiah, bring him some exotic gifts, and look what happens. No respect, no appreciation for the rule of law.

If you’re having trouble generating any sympathy, it may help to learn a bit about these gentlemen.

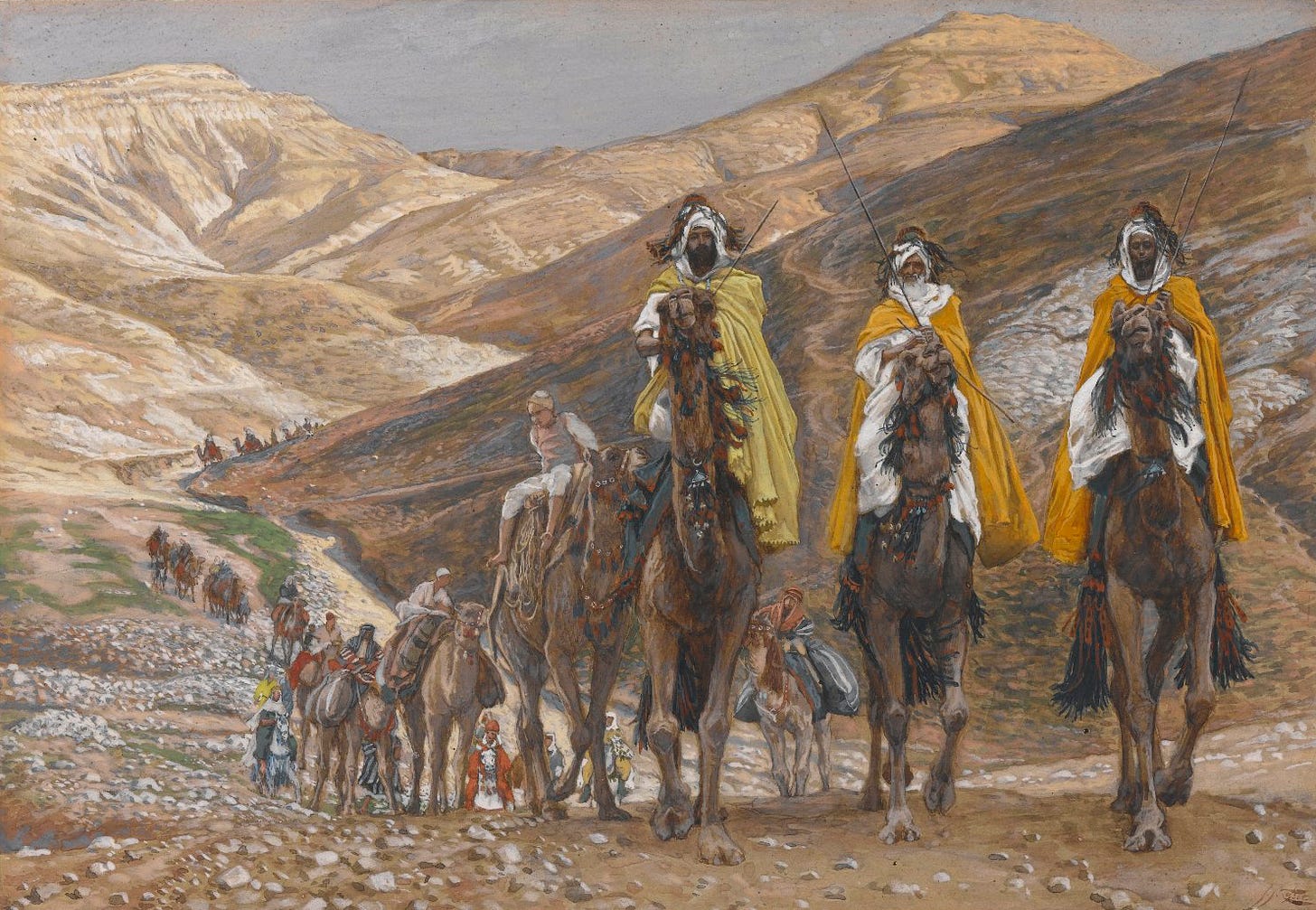

For example: were they even “kings”? Or “wise men”, for that matter? We’re not actually sure. The Gospel of Matthew (2:1-12) refers to them as "Magi" from the East, who saw the star signaling the birth of the King of the Jews and followed it to Bethlehem.

When we say “Magi” here, we are very likely talking instead about scholars or priests of some sort, rather than actual kings. In fact, some believe that what we really might be talking about turn-of-the-millennia astrologers who derived cosmic and religious meaning from the movements of the stars, including that giant one that was apparently shining out in the West that led them to Mary and Joseph’s lackluster Airbnb in Bethlehem.

Over time, though, the Magi got a bit of a makeover. The King James Bible translates "magi" as “wise men,” and that’s what they’ve tended to be referred to. They were given names in various accounts: Caspar, Melchior, and Balthazar. And in Christian art and folklore, they came to increasingly be depicted as kings as early as the third century.1 This is apparently due to the increasing association of the word "king" with the royal gifts they brought, and their starring roles in the story of Jesus' birth. In fact, the idea that there were three magi very likely comes from nothing more than the detail that they presented three gifts; the Bible doesn't actually specify the number of magi. Personally, I like to imagine just one really overzealous gift-giver; or better yet, a dozen of them, only three of whom were thoughtful enough to pack the gold, frankincense, and myrrh (or maybe they got free carry-ons thanks to airline points).

Of course, the symbol of Christ Himself as “King of the Jews” is tied in tightly with these myths, and lends a great deal of thematic heft to the idea of that he would be visited upon, and adored by, earthly kings in their own right. At the very least, the classic hymn “We Three Kings” leans on this heavily:

Born a King on Bethlehem's plain,

gold I bring to crown him again,

King forever, ceasing never,

over us all to reign.

As for whether they were “Kings of Orient,” it’s pretty questionable. Caspar, Melchior, and Balthazar (if those are your real names) have been said to come from a wide variety of places over the centuries. Matthew says they came "from the east," which, geographically speaking, is not that helpful, as “East” is a relative term. “Orient” traditionally implies “east of Europe,” which also doesn’t help that much.

If we dig deeper, we find the Armenian tradition, which poetically refers to “Balthasar of Arabia, Melchior of Persia, and Caspar of India.”2 This implies, again, another great story: all three travelers were inspired by the same star, and traveled from far and wide, independently of each other, to seek it out and bestow complementary gifts upon the Messiah. Other interpretations went even further, mythologizing that the three “kings” came alternately from Europe (Melchior), Asia (Caspar) and Africa (Balthasar).

But back we come to historical and biblical accuracy, and the story comes back down to Earth. If they existed at all, the Magi were more likely to have been learned men of some kind or another who were interested in following the stars to salvation, rather than actual reigning monarchs looking to the next “King.” The long and short of this: all this stuff was so long ago that there’s really no way to know for sure.

Even so, I don’t want to sound like a Grinch. I’m not here to yuck anybody’s yum on Christmas lore. Myths are important, and make societies—and religions—what they are. They produce art of the sort we’ve seen above—the paintings, and etchings, and poems. Why should they not have been kings? Why should there not have been three of them? The power of a good story matters, and a story can give us deep Truth (with a capital “T”) without being technically, historically, scientifically accurate. I say this as a scientist.

And even if they weren’t kings, who gives a damn? They were nice enough to bring expensive gifts to the baby shower, and that’s good enough to me. I’ll happily go along with any story with a central message of “peace and good will towards men.” Go off, Kings.

Ashby, Chad (16 December 2016). "Magi, Wise Men, or Kings? It's Complicated". Christian History | Learn the History of Christianity & the Church.

Nersessian, Vrej (2001). The Bible in the Armenian Tradition. Getty. ISBN 978-0-89236-640-8.

Charlie

Always enjoy the read!

Merry Christmas!

Gerry

Ah, the olive wood crèche. Your grandparents brought it back from their trip many years ago to the Holy Land.