Vacation homes, voter fraud, and Mary Oliver

Bending the rules of democracy in a wealthy Cape Cod beach town

Back in the fall of 2018, I got to spend some time on Cape Cod with a few friends. Despite my unimpeachable credentials as a native New Englander, our family never spent much time on the Cape. Probably it was too far and too expensive; not a place that we could ever call home, lovely though it may be. My friends and I spent most of our time in and around Wellfleet, a small beach community about halfway between the "tip" and "elbow" of Cape Cod. It’s one of the most special places I’ve ever had the pleasure of visiting.

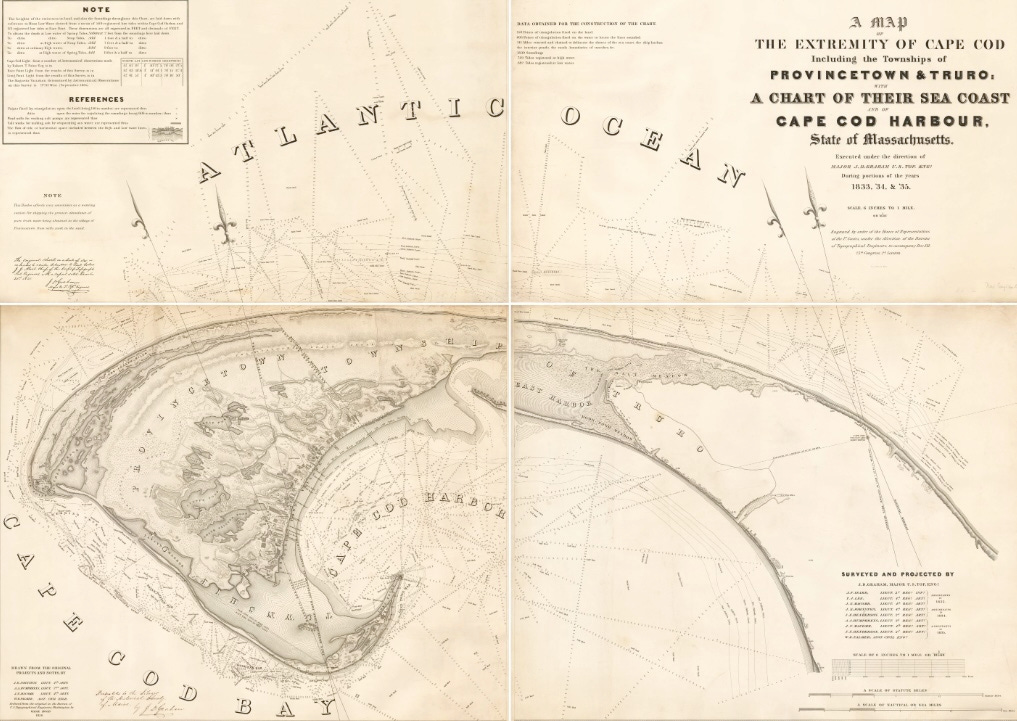

There are just two other small towns farther out on the Cape from Wellfleet. One is Provincetown, the place synonymous with the late beloved poet Mary Oliver. Oliver lived quietly there from 1964 through 2014, moving just a few years before her passing in 2019. According to her neighbors, she was a pretty reclusive member of the community, but also a consistent and beloved one who lived there year-round. Oliver’s work of being a poet was and will always be defined by her hours of time spent walking in the picturesque lands and beaches surrounding the town:

“Go out on the beach at 5 in the morning. That’s how you run into Mary,” remembered Nan Cinnater, the lead librarian at the Provincetown Public Library.

Oliver was known for taking long, pre-dawn walks — walking for hours along the beach, or in the Provincelands.

Those early morning walks produced poems describing the aching beauty of the beaches, Provinceland Dunes, and the Blackwater Woods outside of town, the latter of which spawned a collection of poems that won Oliver a Pulitzer Prize in 1984. Even the few poems that don’t catalog her long walks in nature rely on her attachment to Provincetown and homesickness at being away—like this excerpt below from a favorite of mine, fittingly entitled “Coming Home”:

When we are driving in the dark,

on the long road to Provincetown,

when we are weary,

when the buildings and the scrub pines lose their familiar look,

I imagine us rising from the speeding car.

I imagine us seeing everything from another place--

the top of one of the pale dunes, or the deep and nameless

fields of the sea.

Oliver’s readers have always felt like they know these places intimately even if they’ve never been there. This is thanks to not just to her talents, but her authentic lived connection to Provincetown and its surroundings. In the same way that we associate Wendell Berry with rural Kentucky, or Langston Hughes with Harlem, Mary Oliver will forever be the oracle of Cape Cod. The place was indisputably her home—thus, she could speak for it, and (I assume) participate legitimately in the culture and politics of the area.

I have many sentimental attachments to the edge of the Cape because of the special few days I spent there in 2018; but unlike the great poet whose work and life embodied the place, I was just visiting. I’m obviously not someone who should have a say in (for example) how the place is governed. But what about the people in between?

In the case of today’s story, “the people in between” is pretty literal. The town of Truro—itself a subject of some of Oliver’s poetry—is flanked by my dear Wellfleet to the south, and Oliver’s Provincetown to the west. Over the past year, the community has been in turmoil over an emerging controversy about voting rights, and what it really means to be a “resident” of a place.

In October of 2023, The Provincetown Independent reported on a data anomaly uncovered by Truro’s election and voting authorities: since 2018, Truro’s number of registered voters has increased by 62%, way above rates of neighboring towns, and above the town’s actual population growth, which had been flat during a similar period. The reason for the spike in the voter rolls, it turns out, was an effort by the Truro Part-Time Resident Taxpayers Association (TPRTA) to register dozens of part-time residents to vote in the small community’s local elections and put a stop to new development in Truro.

What do we know about these new voters? The Independent reports:

Sixty-two of those 119 new voters registered with an in-town home address but an out-of-town mailing address. Based on public records in the town assessor’s databases, the Independent found that 11 of those 62 new registrants are currently claiming residential tax exemptions (RTEs) on their homes in other towns: eight in Boston, and one each in Brookline, Watertown, and Cambridge.

This means that a significant number of these new residents clearly consider themselves to be residents of somewhere other than Truro. These are vacationers who, most likely, rent out their homes as Airbnbs most of the year, then pop in and enjoy the summers Mary Oliver captured so beautifully in her poetry (she captured the winters quite beautifully, too). And yet, despite spending the clear majority of their time elsewhere, these folks were encouraged to register to vote in Truro to influence the town’s policies.

The group’s Vice President Regan McCarthy asserts they’re well within both the letter and the spirit of the law. Voting, according to McCarthy, “is something that somebody decides to do after giving great thought to where they feel they want to exercise their right to vote with the most benefit and meaning to them.”

But David Sullivan, a voting rights expert and former legal counsel to the Massachusetts Secretary of the Commonwealth, sees it differently. What counts in voting residency, Sullivan argues, “is not where a person thinks his or her residence is, or wants it to be,” but instead where the “objective facts” tell us they live. The Cape Cod Times quoted the town’s own state senator, Julian Cyr (D), who had his own reservations about the efforts: “It is deeply worrisome,” Cyr said, “to see an effort by individuals who have much fortune in their lives, who are fortunate to have many residences, subvert the election process of our town.”

So, is the election process really being subverted here? Should we think of this effort as a kind of place-based voter fraud? The answer might not be quite so simple.

Some instances of place-based voter fraud are pretty cut-and-dried. Take the recent comments by Casey DeSantis, the wife of Florida Governor and presidential hopeful Ron DeSantis, who implored residents of other states “to descend upon the state of Iowa to be a part of the caucus, because you do not have to be a resident of Iowa to be able to participate in the caucus.”1 This is clearly not correct and definitely is illegal. All American states legally require you to actually live there before you’re allowed to vote there.

It also comes across as facially undemocratic to most people; including, I’m sure, many legally registered Iowans. The out-of-towners Casey DeSantis was inviting to Iowa can’t claim to know what’s in the best interest of Iowa, because they have zero connection there—other than, I guess, really wanting Ron DeSantis to be president for some reason.

However, McCarthy and the TPRTA deserve their day in court, or at least on this Substack. There really are grey areas of residency that we should be considering, including whether geography is the be-all end-all of political representation. For example, early Americans had to own property in order to vote in a particular place,2 but states slowly shed this requirement throughout the 19th century. I think we can all agree that abolishing the property-holding requirement was a good thing, especially for renters who surely should be allowed to register opinions and votes about policies and officials who affect their lives.

Still, there needs to be some standard. If we’re going to have political representation based on places, then people should be voting in the places they know deeply and actually inhabit, where they can understand the unique needs of the community; not just where they think their vote will have the most impact.

Unfortunately, the laws reflecting these values can sometimes create some less-than-ideal representation. Yes, all states require you to live where you vote; but they also allow voters to register, at most, thirty days before an election. Many, like my home state of Idaho, allow election-day registration. This means that when I moved to Boise in 2019, just a couple of months before a crucial mayoral election, I clearly met the legal requirements in Idaho thanks to my home address. In fact, I could have stepped foot in Boise for the first time on Election Day and voted right then and there, provided I had managed to secure a place to live.

So let’s play devil’s advocate: don’t the part-time Truro residents on Cape Cod—who spend three months every summer in the town—probably have more knowledge about the area than somebody who moves in just before an election, even if it’s ostensibly “full-time”? Possibly. On the other hand, even though I had just moved there, I had made a commitment to stick around; that is, my future self had a real stake in who won that mayoral election, even if my past self was a little under-informed.

The farther down the rabbit hole we go, the trickier the questions get. You might think, for example, that these residency requirements make it impossible for unhoused populations to vote. Fortunately, although these populations face other barriers to voting (like photo ID requirements), most places allow registrations to list homeless shelters, or even street corners and parks where they may be residing, as a home address.

These are thorny questions without perfect answers. In the end, each community has to do the best they can to enfranchise its citizens properly and generously, without accidentally opening up the doors to a DeSantis-in-Iowa-style free-for-all.

In this case, the resentment I felt reading about the part-time Truro voters stemmed not so much from disputable ideas about residency and voter registration; but rather from a deep-seated sense that they’re gaming the system in a way that’s fundamentally undemocratic. They live in Boston, or Cambridge, or Watertown most of the year, and want to be a full member of that community. But because they happen to own a piece of property elsewhere, they seem to want to be double-counted and have influence there, too. As Truro’s own state senator Julian Cyr argued, “our democracy is predicated on the principle of one person, one vote.” Legal or not, common sense tells us this effort just isn’t fair.

On top of this, there’s a second injustice at work here that adds insult to injury: the grim reality that voluntary geographic mobility—epitomized here in the owning of multiple homes—is a luxury reserved for the rich and privileged. Extreme wealth is what’s allowing these folks to wield extra political influence in a community they only live in occasionally. These efforts at influence ring hollow and slightly callous, not just because these people spend most of their time somewhere else; but because they can afford to do this, and the rest of us cannot.3

This fiasco also pulls the curtain back on a deeper, less inherently political repercussion of this inequality: that more often than not, these vacationers can end up warping the culture and legacy of a place to suit their own ephemeral, part-time needs, rather than the long-term needs of the broader community. It’s a phenomenon that Mary Oliver—a full-time, deacades-long resident of the town just next door to Truro—gave voice to in a solemn, biting poem “On Losing a House”:

Amazing

how the rich

don’t even

hesitate—up go the

sloping rooflines, out goes the

garden, down goes the crooked,

green tree, out goes the

old sink, and the little windows, and

there you have it—a house

like any other—and there goes

the ghost, and then another, they glide over

the water, away, waving and waving

their fog-colored hands.

Again, there’s no one answer here, and different communities have nuanced opinions about voter registration and residential status. Maybe, since these folks spend a quarter of the year on the Cape, they should get, say, a quarter of a vote there. But until we find a way to implement such a radical idea effectively, I’m content erring on the side of Mary Oliver for the time being.

Mrs. DeSantis later insisted that she was only talking about volunteer activities like phone-banking and door-knocking, not about voting itself.

And, of course, be a white man of a certain age.

This eminently blessed community of second-home-owners represents, according to the National Association of Home Builders, only about 5% of Americans.

Hi Charlie. Excellent and nuanced look at this issue. I would add a couple of points: In Massachusetts if you enroll to vote in one town, you lose the right to vote in wherever else you live. So there’s that. However that caution would be destroyed by same day registration, which I never had an opinion about until I watched Wild, Wild Country, a documentary of the sannyism cult in Oregon, which flew massive amounts of homeless people into the community to register and vote on same day registration. THe cult took over the town. They also later poisoned the some of their enemies, so this was really off-the-charts evil and not your average voter issue, but still. As well as it worked out for you, and your good intentions, I think same-day registration opens the floodgates to voter fraud. If you haven’t seen it, you should watch it. It came out probably half dozen years ago and is quite powerful.

I was just sharing your substack with a friend of mine who said she wrote her masters thesis on Mary Oliver, but had to defend her heartily as she was “commerical.” Nothing more suspect than a successful poet. The arm of the Cape has always struck me as a little too remote for my tastes, but perhaps a revisit next time I’m nearby. Enjoyed your writing today!