I’m sorry to spring this on you, but it’s my birthday this Sunday, December 10th. No, you don’t have to get me anything—I’ve never been a huge birthday celebrator (though you’re welcome to subscribe to my newsletter if you haven’t already).

That said, I do share the day with a number of dignitaries like Bobby Flay, Meg White, and Raven-Symone. Ada Lovelace, the badass daughter of Lord Byron who wrote first computer program, was also born on the 10th.

The person I’m most honored to share a birthday with, however, is the greatest poet who ever lived, Emily Dickinson. I love many poets, but I have loved Emily most of all since well before I learned that we were born on the same day of the year. I can’t complain about turning 35 on Sunday—it’s an age I’m happy to be, especially since Emily will be turning a ripe old 193. Plus, even if some technological wonder allowed me to live that long, I couldn’t come close to expressing myself as magnificently in that lifetime as Dickinson did in even one of the 1,800 (that’s not a typo) poems she wrote in her relatively short lifetime.

With a couple thousand poems to her name—and nearly all, devastatingly, unpublished until after she died—Dickinson covered just about every topic imaginable. But one topic she returned to again and again, and to which I’m relating heavily this week, is books: their shape, their power, and their limitless capacity to free us and explode our perspectives. It can be difficult these days, or any days, to communicate the importance and transcendence of a good book in a way that isn’t trite or stale. And I am not a poet, so I won’t try; but luckily we have a variety of examples from my birthday bestie to help us out. Here’s one, from “He ate and drank the precious Words (1587)”.1

He ate and drank the precious words,

His spirit grew robust;

He knew no more that he was poor,

Nor that his frame was dust.He danced along the dingy days,

And this bequest of wings

Was but a book. What liberty

A loosened spirit brings!

In this poem, the book is the subject’s sustenance (“He ate and drank the precious words”); it grows his spirit, transcends his poor wealth, his poor health, and the “dingy days” of his environment. We often think of books lovingly as things we can tumble into and shrink inside, which is true—but Dickinson sees their power as escaping outward rather than just collapsing inward.

How does she get this quality across? Dickinson was a master of metaphor, and her poems about books exemplified this. Her approach was often to personify the books in her poems, or otherwise to cloak them with dynamic qualities and abilities. These books are more than just static, non-living objects of our affection; rather, they are fully-embodied, action-taking beings with their own life and unique power. In this case, a book is a “bequest of wings.” This echoes maybe Dickinson’s best-known poem, in which she speaks of “hope” as “the thing with feathers,” an empowered vessel that can go anywhere.

Birds are one of Dickinson’s favorite motifs, but they aren’t alone as the embodiments of Dickinson’s musings about the power of books. In “There is no Frigate like a Book (1286)”, for example, she invokes not just boats (“Frigate”2) but horses (“Coursers”3)

There is no Frigate like a Book

To take us Lands away

Nor any Coursers like a Page

Of prancing Poetry –

This Traverse may the poorest take

Without oppress of Toll –

How frugal is the Chariot

That bears the Human Soul –

It is difficult, when reading this poem, not to think of libraries, since Dickinson talks about books as a universal commodity—a mind-expanding journey that can be taken “without oppress of Toll” that even “the poorest” may take. Books can be expensive to buy (otherwise I would have an even more unacceptable number of them than I have already), but libraries—at least in theory—give even the least-resourced among us the superpower of diving into new realities at no cost.

But here is Dickinson’s genius, with a double-meaning behind “frugal.” Not only is a book a frugal (that is, thrifty) way to explore new or undiscovered worlds if you don’t have the means to do so; but as a vessel for ideas (“the Chariot/that bears the Human Soul”), a book is also frugal (that is, efficient)—small outside but mighty within, “contain[ing] multitudes” like Dickinson’s contemporary, Walt Whitman. For the Doctor Who fans out there, I’m reminded of the time-traveling Doctor’s home and spaceship, the TARDIS, which on the outside appears to be a tiny phone booth that a person could barely fit inside; but which is literally, physically “bigger on the inside,” with cavernous rooms full of technology, centuries of stories, and—one must assume—libraries of books that, like that TARDIS itself, transcend space and time.4

Not being a time-traveling alien herself, Dickinson lived a quiet, reclusive, stationary life in Amherst, Massachusetts. Her grandfather, Fowler Dickinson, was one of the principal founders of Amherst College; and by all outward accounts Emily lived a comfortable but (to the outsider) boring life. For all the wandering she did in her poems, biographers tell us that she “rarely ventured beyond the family Homestead.” To me, this makes it all the more poignant, important, and a little bit comforting that in her writing, she embodied the expansion and exploration that eluded her in her home life. This limitless sense of discovery infused her writing about life and love, about people, and about the books that, for her, were a world even more tangible and expansive than her more cloistered physical reality.

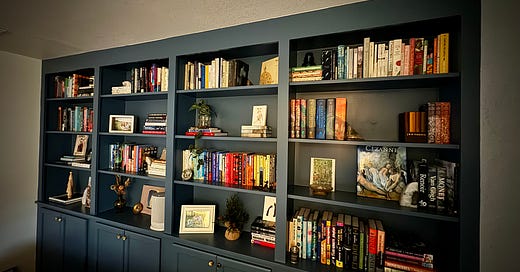

One reason I’m thinking about these poems so much is that my wife and I just had built-in bookshelves installed in the far wall in our front room. It was something we knew we wanted to do since we bought the house this past February—in fact, I’m pretty sure we had the idea when we first toured the place last year.

Before these beauties came to fruition in November, our excess books—of which there were many—lived in cardboard boxes in the garage. They existed, and we knew they were there, and we had read many of them, but they weren’t active parts of our home life. As we’ve carefully and intentionally placed these books on the shelves alongside plants, photos, and other decorations, we’ve established a little library that we can go to anytime we want.

We know, because of Dickinson’s poems and our own intuition and experience, that books can take us to faraway places inside our heads and out in the world. But having a sacred space or spaces to put our books where we can see them, touch them, and sit next to them, speaks to a second great power that books have, especially when they’re with you in the home. A “bequest of wings,” yes—but also an anchor, helping to hold us in a space and keep us grounded in possibility.

Dickinson can help us unpack this even more in a final poem, “Unto my books so good to turn (604)”:

Unto my books so good to turn Far ends of tired days; It half endears the abstinence, And pain is missed in praise. As flavors cheer retarded5 guests With banquetings to be, So spices stimulate the time Till my small library. It may be wilderness without, Far feet of failing men, But holiday excludes the night, And it is bells within. I thank these Kinsmen of the Shelf; Their countenances bland Enamour in prospective, And satisfy, obtained.

I think that, even more so than the other poems we’ve looked at, this one is relatable on a few levels.

Take the first stanza: who among us hasn’t, at the end of a long day at work, longed to collapse into a stack of books? Dickinson takes on an “absence makes the heart grow fonder” mentality to the books that await her after her daily work: so deep and rewarding are their contents that the anticipation and “abstinence” from them are “half-endear[ing].” Like catching a whiff of dinner before “banquetings to be,” her “small library” (like the lovely one we just had built in our home) is so enticing that even the longing for it is a fulfilling state by itself.

Later in the poem, Dickinson reiterates that books “enamour in prospective” throughout the day when you aren’t reading them; then, when you actually “obtain” them, live up to the hype and ultimately “satisfy.” This is good news for junkies like me (and I’m guessing many of you) who seem to get as much pleasure out of ordering books they don’t yet have rather as they do from reading any of the unread dozens already sitting on the shelf.

Finally and most importantly, it’s fitting that we get from Dickinson a final incarnation of books as fully-embodied people, “Kinsmen of the Shelf”. In addition to taking us to far-flung places—in boats, on the wings of birds, or even in spaceships—books can act as friends and loved ones who keep us grounded, and keep us company, too. This is a magic of books that I think is often overlooked: they can take us places outside of space and time while also anchoring us where we are. Even beyond the words within, books—on shelves, at bedsides, and even in chaotic stacks—create physical spaces in the real world that keep us rooted, and give us something (and some place) to look forward to.

I’m finding that our own “small library” of new bookshelves is serving a similar purpose for me. The world lately has felt dark, unpredictable, and chaotic, leaving us feeling overwhelmed and undernourished. But Dickinson assures us that reserving spaces like these, surrounded by the safety and sustenance of books, can help us weather the “wilderness without.” For us, this could be violence in the Middle East, threats of literal dictatorship at home, or yet another record-breaking year for mass shootings. For Dickinson, as it was for Whitman, it’s the “Far feet of failing men” fighting unimaginably bloody battles in the American Civil War.

We don’t have to (and shouldn’t) turn away from these conflicts, and it goes without saying that our leaders might be better-equipped to solve them if they bothered to surround themselves with a book or two. But Dickinson has shown us that books are useful on both fronts of this struggle: they can help us venture out like intrepid explorers, to other worlds that we can use our too-short lives to change; all the while, books and book-filled spaces offer us the occasional refuge and safety of a friend.

And what steadfast friends they are. Happy birthday, Emily.

Dickinson didn’t title any of her poems, and scholars have resorted to a number of methods of referring to her specific poems over the decades. The most common appears to be referencing the first line of the poem, and the apparent numerical timing of the poem in her lifespan, which I’ll do here and with her other poems I reference in the post (and future posts, wherein I assure you Emily will pop up again).

“Courser” is a common term from the middle ages for a “swift or spirited horse.”

In fact, we see the library in the otherwise-lackluster episode “Journey to the Centre of the TARDIS.”

This may be obvious, but here she means (in the parlance of the time) something much closer to “slowed down” or “dulled by being famished” rather than the more modern pejorative for “developmentally challenged” that has thankfully been all but banished from civilized society.

Happy Birthday to you, Charlie! Will you be having chocolate cake?

It's delightful to see your bookcase, and it is indeed very stylish. I've also chosen black shelves - they add a sort of gravitas to the books I think. Thanks for sharing your review of Emily Dickinson's bookish work, I really will get around to reading more of her work next year when I have more time.

I’m a “vanilla cake, chocolate frosting” kind of guy, but I’ll take what I can get :) I agree that darker shelves can help the books really stand out... and they’re the stars of the show, after all!