Older readers might remember our colorful former Speaker of the U.S. House throughout the 1980s, Tip O’Neill. Though he was Speaker, and a national figure in his own right, O’Neill is famous for the old adage that “all politics is local.”1

By this, O’Neill basically meant that at the end of the day, politicians outside of the president are re-elected not by national constituencies, but by the ones in the districts and states they represent. As a result, the most successful and effective lawmakers are 1) in tune with their own voters, 2) constantly keeping their finger on the pulse of their districts, 3) fostering good relationships with local media, and 4) demonstrating an understanding of unique local issues, and ideally a commitment to solving them; by crossing party lines, if necessary.

O’Neill served in Congress from 1953-1987. A long and admirable career, but one that should lead us to question whether O’Neill’s “all politics is local” advice is evergreen, or just a thing of the past.

To answer this question, we need to understand a key process of American politics that’s bloomed over the past half-century, and which has everything to do with geography. That process is called political nationalization: essentially, the reversion of O’Neill’s political advice all the way to the other end of the spectrum. It’s the idea that our politics is defined not by local issues, local party organizations, local media coverage, and local voter-to-representative relationships; but instead by the broader national versions of those forces.

Let’s look at this development through a few of these lenses, and with the aid of some handy charts.

Our party viewpoints have nationalized

First, I should make clear that “nationalization” and “nationalism” are very much not the same thing. The latter is an ideological point of view; essentially, that nationality (i.e. “being an American”) is the one true identity that matters the most for voters and representatives alike, and that the only consideration worth making is whether something “benefits Americans” or it doesn’t.

Nationalization, on the other hand, does not mean that we are nationally unified, or that “place” doesn’t matter at all. Instead, think of it as a filter through which all of our political considerations, behaviors, and decisions flow. Essentially, nationalization means that our political life is viewed through the lens of national-level divisions rather than local ones. And in our case, these national-level divisions are, increasingly, partisan ones that didn’t used to dictate every last one of our political disagreements.

Let’s look at what this means through the lens of lawmaking in Congress. It used to be that conservative Democrats from the South could form broad coalitions with other Democrats, plus more moderate Republicans, on grand pieces of domestic legislation (think FDR’s “New Deal” or Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” programs). They could do so without worrying about their support or opposition of the President affecting how the voters in their districts felt about them.

For some evidence of this, take a look at the chart below, which tracks the percentage of members of the U.S. House who are in the same party as the president (dark blue) and of those in the opposing party (light blue) who voted in support of the president’s position on a policy matter on the floor of the House. In the 1950s and even up through the late 1960s, the party affiliation of a member of Congress told you very little about how likely they were to vote with the president on a given issue. That is, presidents received nearly as much support for their policies from members of the other party as they did from their own party.

Fast forward to 2016. The president (Barack Obama) is having a nearly impossible time winning over members of the other party, and meanwhile is enjoying record levels of loyalty from members of his own party. There are a million reasons for this, but some of the most potent ones are geographic, and a direct reflection of nationalization.

In this case, the two major parties are becoming more homogeneous. In other words, Republicans are becoming more similar to each other—that is, conservative—and Democrats are doing the same on the other end of the spectrum. We no longer have a mix of conservative and liberal Democrats, and conservative and liberal Republicans, which is bound to produce (for example) a bunch of Republicans crossing party lines to vote in favor of civil rights during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, or a bunch of Democrats voting in favor of tax cuts during the Reagan era.

By mirroring their liberal and conservative tendencies, the Democrat and Republican party labels mean something much more concrete now, and they mean the same thing in different places much more than it used to. A Louisiana Democrat and Massachusetts Democrat used to be as different as can be; but nationalization means that a Democrat is a Democrat, almost regardless of where you live. The result of this is two parties who, across the board, are very loyal to their national leaders (presidents and presidential candidates), rather than localized ideological leanings.

Our elections are nationalized

A big part of why we see this behavior in Congress is that voters are incentivizing it by nationalizing themselves. We can see this clearly in our elections over the past 50 or so years.

Take the House of Representatives, that paragon of organization and responsibility. In the chart below, we see the trajectory of two types of congressional districts. The dark blue line is the number of districts that selected the same party for president, and for the House. The light blue line is the number of districts that split tickets; meaning, they voted for Joe Biden, but elected a Republican to Congress (or voted for Donald Trump, but elected a Democrat).

In the 1960s and 1970s, you see not a majority, but quite a lot of split-ticket voting. In 1972, for example, almost as many districts split their tickets as voted for the same party for president and U.S. House. As recently as 1984, tons of districts that elected Democrats to Congress also voted for Ronald Reagan’s reelection.

This practice was nearly unimaginable in 2020. Out of 435 congressional districts, only a couple dozen split tickets, voting for Joe Biden for president but a Republican for Congress; or Donald Trump and a congressional Democrat. Nearly all the others went all-Democrat, or all-Republican.

What does this tell us about our current, nationalized politics? Well, as recently as the 1980s, voters were clearly selecting their candidates for office based in part on local concerns other than the national party label. After all, if your party dictated who you voted for, you wouldn’t vote for Ronald Reagan *and also a Democrat for Congress*. You’d pick one or the other.

Today, however, a Trump-supportive district is very unlikely to elect a Democrat, and vice versa. The chart above tells a story of a near-total alignment of elections and voting patterns around national partisan politics. Whether someone identifies mainly as a Democrat or a Republican, is now the overriding factor you’d want to know in order to predict how someone will vote not just for president, but for every other office. In other words, voters are using the same criteria to select their representative for president as they are for virtually every other office.

This, by the way, is why we see the policy voting trends in the first chart. If you’re a Democrat in Congress, and you know your voters are selecting you based solely on your loyalty to the party platform and Joe Biden, how likely are you to oppose him? How likely is a Republican to turn against Donald Trump? The incentives, increasingly, just aren’t there.

Our issues are nationalized

Sure, we’re really deeply attached to our party affiliations (or at least, deeply distrustful of the other party); but don’t local issues matter? Don’t local political environments matter in shaping people’s issue positions?

The answer, it turns out, is less and less. Increasingly, the public’s opinion on virtually every issue is filtered through a red or blue lens, dictated by national partisan considerations rather than local needs.

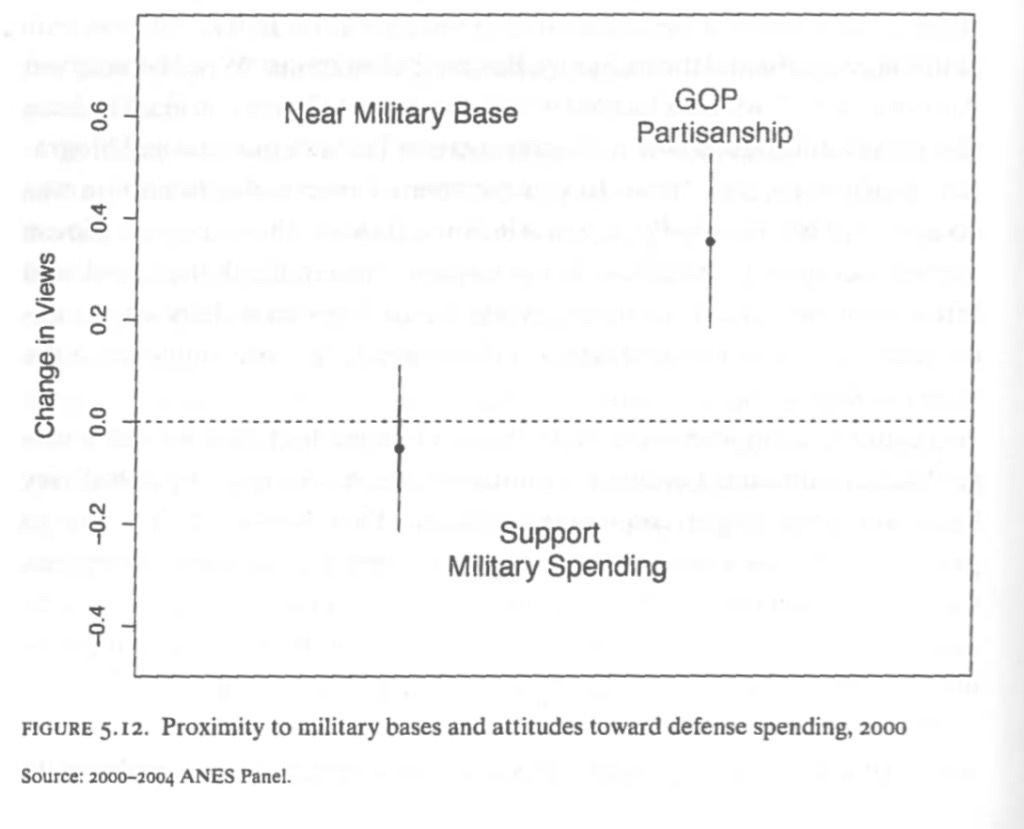

Take the analysis that fellow political scientist David Hopkins conducted looking at public support or opposition for more military spending based on how close a voter was located to a military base. We would think that voters closer to military bases, which depend on government funding and which support the local economy, would be more likely to support higher military spending than those far away from these bases. But that’s not what Hopkins finds.

Instead, Hopkins finds that partisanship — specifically, party identification with the Republicans — is much more predictive of higher support for military spending than close local proximity to a military base. The latter has almost no effect.

It used to be that politicians ad voters alike were more likely to interpret big national issues through a local lens: “How will the mew federal budget affect my district? Will the new energy legislation force my county’s coal plant to close? Will the new infrastructure bill mean new jobs for my district?”

Today, it’s the reverse. Rather than viewing national issues through a local lens, we’re increasingly viewing local issues through a national lens. We’ve witnessed, over the past couple of years, local governments like city councils and school boards wrestle with local education issues through the lens of hot-button national disagreements around COVID policy, book banning, and efforts to marginalize trans youth. Hopkins’s excellent book has a variety of evidence showing that national partisan attachments are more predictive than ever of viewpoints on apparently-local issues, rather than local influences (like proximity to a military base).

Our political media is nationalized

Finally, we are probably all aware in some way that our media ecosystem is nationalizing. My dad, who has since (thankfully, deservedly) retired, worked for most of his life at a regional New England newspaper that has declined massively over the past several decades. It’s not alone. The market for state and local news has plummeted just in the last 20 years, as the chart below demonstrates. By some estimates, one-third of American newspapers that existed two decades ago will be out of business by 2025.

Meanwhile, there has been—as the chart below from FiveThirtyEight tells us—a “trickling-up” of news influence by the top few news organizations in the past decade or so. The result? Skyrocketing influence of big national outlets like the New York Times and Washington Post. Americans are simply paying more attention (and money, for that matter) to national news and national outlets, and less to more local and even state outlets. The Post and the Times are both fine publications, and I read them regularly; but they don’t do a great job covering the Idaho state house or the Boise city council.

Is any politics local?

These trends are pretty clear, but we also know that they have their limits and exceptions. Much as Democrats and Republicans in Congress seem unified against each other nationally, we still have—and will likely always have—our Joe Manchins and Susan Collinses to buck the trend and establish locally-tied reputations. In fact, I wrote an entire book on the subject, which shows pretty clearly that there is still room for locally-tinged representation, and that this brand of representation is absolutely necessary for a functioning political society. Voters still care about local attachments (just ask Dr. Oz), and the parties would be wise to honor these wishes by nominating homegrown candidates. I would argue that Manchin and Collins, for example, have only been able to survive so long because of their local roots in West Virginia and Maine, respectively.

But some of the issues associated with nationalization are much, much trickier to solve. Local, high-quality journalism is absolutely essential to good governance and a free society, but I have no idea how to save it; the parties continue to calcify and polarize at the national level; frustration with them is reaching a fever pitch, and yet there remains no clear path for a third party to be successful, at least not yet.

I’m reluctant to say that nationalization is wholly a bad thing that should be eradicated completely. For example, it creates some kind of a shared reality that all Americans can use to relate to politics, and there’s evidence that the partisanship associated with it has increased election turnout and made the average American more attentive to politics, particularly over the last decade.

And yet, I’m skeptical of any political phenomenon that takes us out of where we live and into a no-holds-barred panopticon of partisan fighting. Nationalization, for all its potential benefits, is doing this. And it’s important to understand the process if we want any hope of surviving this great “dis-placement.”

The phrase and its variations surely didn’t originate with O’Neill, but he definitely popularized it in the 1970s and 80s.

Fascinating column. I’d really like to see another one on the role of social media on all this. I worked for a former congressman who became the president of UMASS and have heard him say that he left because once social media came in, you could no longer work across the aisle.