Do voters move away from places because of politics?

The answer is "sometimes", but (shocker) it's complicated.

“It’s a beautiful state. The mountains, the lakes, the rivers, the beaches. All are overshadowed by the societal and political climate.”

So wrote Steve Huckins, an Oregon native who was profiled in a recent New York Times article that got a fair bit of attention. In a heartfelt Facebook post to his friends, Steve was saying goodbye to his home state in favor of Missouri. Huckins and his wife had lived in Portland for decades, but moved because they could no longer stand the politics of the state and the city they had called home for so long.

Picking up and moving 2,000 miles to get away from the liberals is a serious decision; and to their credit, I’m sure it’s not one that the Huckins family took lightly. The same, I’m sure, is true for the other family profiled in this article—the Nobles—who left their native Iowa after the state banned gender-affirming care for minors in 2022. This ban included the prescription testosterone that their son, Julien, was currently taking to aid with his transition. In the case of Jennie Noble, Julien’s mother, there was no doubt about why they were leaving: “We are moving to Minnesota where the laws are more favorable,” she says in the article.

These families’ stories are interesting and affecting, but do they signal a real phenomenon? Are voters across the country, feeling politically displaced and alienated, picking up and moving to more friendlier environments? Is this what’s causing the geographic divides that have come to define the country over the past couple decades?

Luckily, political science has some theories, and maybe even some answers for us. Let’s get into it.

I don’t know if you guys know this, but we’re a pretty polarized country. We’re polarized on ideological lines, party lines, and racial lines. We’re divided on religion, on where we shop, and on which movies should win the Oscar for Best Picture.

We are also, as many of us know intuitively, polarized based on geography. This polarization plays out in patterns that even the highly politically aware among us might not think about every day, but instead take for granted as political realities: Democrats cluster in big cities, while Republicans tend to win easily in rural areas. Massachusetts is a blue state, Idaho is a red state. Pennsylvania is a swing state; its much-maligned neighbor New Jersey is not. The coasts are liberal, the heartland is conservative. We’ve seen the maps, like the one below, telling us what we already know deep in our bones.

These are all, of course, oversimplifications of all of these places, but that’s a post for another day. What we can be sure of is that these patterns really do exist. Republican candidates have won Arkansas, and Democrats have won California, in every one of the past six presidential elections, and we know that this isn’t the result of mere chance. Places are political—and, increasingly, partisan—one way or the other.

So, how did we end up with these patterns?

One explanation for why Democrats live some places and Republicans live in others, is that this is what they’re choosing to do. In other words, they’re the Nobles and the Huckinses, recognizing a political misalignment between themselves and where they live, and then correcting it. We can call this explanation the Selection Hypothesis—voters are actively “selecting” into and relocating to places that align with them based on factors like their party affiliation, or whether they see a place as more liberal or conservative. In this view, explicitly political considerations like party identity and ideological leanings come first as motivators for potential movers.

It makes sense, of course: we can all relate to wanting to be around people who think and vote like us. But do people actually make real-life relocation decisions on this basis?

Whole books have been devoted to this question, but I’ll try to boil things down for us using one of my favorite studies from my former University of Maryland colleague Jim Gimpel and the late (great, genius) Iris Hui. They use a fascinating experiment to show that partisanship really can be a motivating force behind relocation decisions. They use an experiment to randomly present a few different (but comparable) groups of Americans each with a listing of a home they could prospectively move to, complete with a picture and statistics about the neighborhood (racial composition, socioeconomic status, etc).

In this experiment, though, they show everybody the same picture and statistics. The only characteristic they vary from group to group is language about the partisan balance of the neighborhood—for example, one group is told it leans heavily towards Democrats; another, that it favors Republicans; and another still that the vote tends to be mixed. Gimpel and Hui find that voters who identify as Democrats and Republicans both are more likely to signal a willingness to move to a place that is more favorable to their own party. In other words, Democrats are more likely to want to live in the same place when they’re told more Democrats already live there, and vice versa for Republicans. Independents, meanwhile, are equally likely to want to live somewhere regardless of its reported party affiliation.

Taken together, this is a pretty clear confirmation of the Selection Hypothesis: that purely political considerations like party affiliation serve as “a moderating factor” in voters’ motivations for where to move—and, of course, where not to move. In other words, the Nobles and Huckinses are not alone. They, and apparently many other voters, are ready and willing to consider partisanship and ideology when considering the momentous decision of where to live.

Not so fast, though. If you were a particularly attentive student in my class (a rarity), you might raise your hand at this point: “But Dr. Hunt,” you might say, “do people really know what the partisan makeup of a neighborhood is? Like, is this a realistic experiment?”

Very astute, fictional student. Ten points for Ravenclaw.

Sure, I won’t deny that I spent a good bit of time looking at the New York Times' precinct-level map of the 2016 election1 before moving to Idaho from Washington, DC. However, 1) sad though it is, I didn’t have any other job offers besides Boise State, and beggars can’t be choosers, and 2) I literally do this stuff for a living, so this is (alarmingly enough) normal behavior for me. Most Americans, thankfully, are not poring over red-and-blue-tinged maps, investigating the exact percentage of the vote Joe Biden or Donald Trump got in their neighborhood in the most recent election.

For another thing, moving—particularly to exactly the one place you desire in the entire country—is an extravagent luxury that not all, and probably very few, Americans have. Take my current home state of Idaho, where wealthy conservative Californians are coming in droves, ostensibly to escape the horror of progressive Gavin Newsom-esque politics. They’re coming from increasingly blue cities like Sacramento and Los Angeles, and even non-California Democrat-havens like Phoenix, AZ. Yes, this is totally happening (I can vouch for it personally); but it’s a choice afforded only to those who can literally afford it—for example, retired Boomers with millions in home equity in major markets like LA and Phoenix. For most others, moving means changing jobs and spending thousands on moving costs, not to mention sacrificing relationships with family and friends.

Even beyond basic cost concerns, we know intuitively (and probably from experience) that Americans’ mobility decisions are influenced by a huge variety of other factors. The unique “feel” of a neighborhood; the proximity of the neighborhood to coffee shops, or a Target, or a mall; how quiet or bustling the neighborhood is. How our partners, our families—Christ, how our pets (see above)—might feel about it.

So, as much as people might say they’d be willing to move somewhere else purely because of politics, we know this can’t be the only reason we’ve ended up with our polarized places.

Luckily, we have some other cool explanations that can help us sort this out.

Unlike the Selection Hypothesis, others argue that political considerations like party or ideology are not the driving force behind our geographic polarization; rather, our political behaviors and attitudes are mediated and dictated by our social environments. These environments include things like how densely populated a neighborhood is; the racial and socioeconomic makeup of an area; and the cultural influences that make the place what it is.

These factors are important to a lot of us, and can be really influential. They help formulate the character of a place, make its culture and space unique, and give it a real identity. Just as importantly, they feel different from a blunt-force consideration like “how many Democrats live here?” So maybe it’s these more deeply-ingrained features of a place, and not its politics, that influence us, rather than us choosing to live somewhere else because of politics.

But at this point—and this is important—politics and place are not actually all that different. This is because of a process that’s been unfolding over the past half-century or more called partisan sorting.

My students never truly believe me when I tell them this, but it used to be that the Democratic Party contained a mix of liberals and conservatives; white and nonwhite voters; and, yes, urban and rural folks. You couldn’t reasonably guess the party somebody regularly voted for just based on these other identities and opinions. But over time, the two parties “sorted” on these demographic traits. Democrats increasingly became the party to join if you had progressive policy viewpoints; Republicans, meanwhile, became the party of “family values” and traditionalism. Nonwhite Americans came to understand—for better or worse, right or wrong—that the Democratic Party was the one for them. Conservative whites found a home with the Republicans. The same sorting happened, and continues to happen, based on geography.

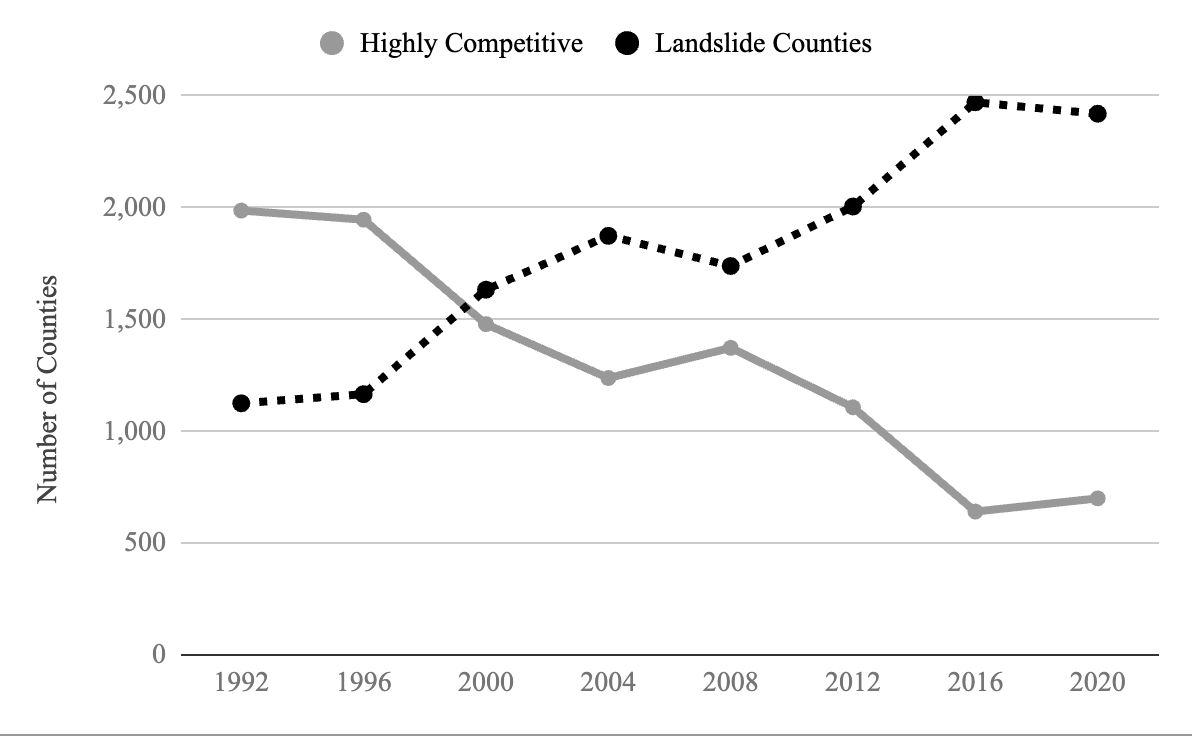

Take the handy chart I made below—I confess it’s one of my favorites. It shows the trajectory of 3,000+ American counties, whose boundaries generally stay the same over the decades; specifically, how competitive these counties are between the parties in presidential elections. The solid line indicates counties that are true toss-ups, not consistently won by one party or the other; the dotted line, landslide counties that Democrats or Republicans nearly always win.

You don’t need to be a political scientist to notice the pattern. In my lifetime, fewer and fewer places in America are truly up for grabs between the parties; meanwhile, more and more of them are strongholds for Democrats or Republicans.

This is geographic sorting in a nutshell. From the 60s through to the 90s, liberals in urban counties eventually left the Republican Party and voted with the Democrats; meanwhile, rural conservatives in Southern counties—once bastions of support for the Democratic Party—fled for the GOP and haven’t looked back. Both sets passed these political opinions, and party loyalties, on to their kids, and so on and so forth.

This, then, is our second big explanation, which we’ll call the Sorting Hypothesis. It’s not (or, not only) that people are moving en masse to places that align with their political sensibilities. Instead, similar voters (racially, culturally, economically, etc) are living in similar areas; but over time—and over generations—their party preferences are changing. Communities are “sorting” more neatly and loyally into the two major parties as their ideologies, interests, identities, and preferences become clearer. As social environments and neighborhoods in American places become more clearly one-sided in their politics and partisanship, voters are identifying with the parties that “fit” their neighborhoods’ social structures and cultures, which they have adapted to in their upbringing and fit into themselves. In this explanation, place comes first; partisanship comes later.

Let’s bring back in the Gimpel and Hui study for some scientific backup. We’ll recall that they found party affiliation by itself to be a motivator for many voters; but in an additional experiment, they completely omitted all party information, and instead varied what they showed voters based on the houses and neighborhood information that had (apparently) nothing to do with politics. For example, they showed each comparable group of voters a different photograph (see below) of the home they were being asked to rate in terms of livability. Take a look at these yourselves, and see what you think. Where would you want to move, if you had to?

I’m guessing you have your preferences, even if you’re not immediately sure why. But in addition to these photos, the authors also gave voters varying information about these homes. For example, respondents who were shown the top-left row-house are told that it’s 6 minutes from downtown, 20 minutes from a shopping mall, and more than 50% nonwhite. The group shown the bottom-left photo of the “older two-story with tire swing”, on the other hand, are informed that the nearest downtown is nearly two hours away; a mall is nowhere to be found; and the racial composition is 95% white.

We can see where they’re going with this. The experiment Gimpel and Hui are running is capturing the urban/rural divide without mentioning the two parties. Based on this information, including the photos, we wouldn’t be surprised to learn that the top-left photo is from northwest Washington, DC, or that the bottom-left photo is from a rural farming community in central Kansas.

Respondents made these assumptions as well, and had clear preferences based on this information. Democrats, on average, strongly preferred the more urban-coded locations; Republicans preferred the rural-coded ones. The preferences were clear, divided, and polarized, even in the absence of party information. As Gimpel and Hui put it, voters “are able to make correct inferences about the partisanship of a place” even without the explicit info about the party affiliation of these areas. In fact, when asked after the experiment, most respondents made educated guesses that the top-left photo was from a heavily Democratic neighborhood, while the bottom-left one tended to vote Republican.

In other words, voters understand better than ever what it means for a place to be “Democrat” or “Republican” without needing to be told explicitly. Voters make these distinctions, infer the political leanings of an area, internalize it, and—apparently—move there as a result.

Skeptical? Try this ingenious quiz the New York Times developed a couple years ago, which presents you with a random Google Street View of an American neighborhood, and asks you to guess whether that precinct (generally a neighborhood of about 1,000 voters) supported Trump or Biden in the 2020 election. They don’t even give you the details on income, race, or downtown proximity, but they don’t have to—answer quickly without thinking too much. Because of the partisan sorting that’s occurred over the past half-century, you can make inferences—stereotypical ones, yes—but more accurate ones than ever, about how your fellow Americans vote.

So, do voters move because of their political party? Maybe. But Gimpel and Hui’s point is that voters may do this even when they don’t mean to, based on factors that seem, on their surface, to have nothing to do with Democrats or Republicans. Even when information about how a neighborhood votes isn’t a top-of-mind factor (and let’s face it, for most Americans, it isn’t) they can still make inferences about the “type of place” or the “cultural environment” they want to live in. And these characteristics, more than ever, capture and reflect our deep partisan divisions. Here’s Gimpel and Hui:

Certainly some people will fail to see the political significance of racial composition, and even more will fail to read any political content into knowledge of a property's physical location. But for populations that regularly have the opportunity to move, those whose upward mobility is commonly expressed in geographic mobility, a grasp of these connections may be obvious to the point of requiring only an effortless glimpse.

We know, though, that partisan politics—mercifully—isn’t everything. It’d be a genuine tragedy if it were. There are so many meaningful reasons to move somewhere that have nothing to do with the factors Gimpel and Hui mess around with in their study. As they put it in the conclusion:

A suburb with a good school district and safe streets is a magnet for citizens of both parties, as well as those with less party attachment… [and] even most favorable partisan composition cannot compensate for limited employment prospects, which is why remote rural areas that are colored deeply “red” do not attract more Republican residents than they do.

It’s true. Voters—at least those with the means to do so—can and do sublimate their political opinions if it means a better future for them or their children. Living in a like-minded area is great, but not a big comfort if you can’t find a job, or if your kid’s school is falling to pieces. Plus, we know that even today, plenty of Democrats live in rural areas, and plenty of Republicans live in cities. Donald Trump got millions of votes in LA and Chicago, and Joe Biden got millions in rural Texas—a reality that isn’t discussed enough.

On the other hand, we know that for many people, “moving for the sake of partisanship” means a lot more than just “wanting to be on the winning side of politics.” For Steve Huckins and his wife, who fled Portland for Missouri, this was—on the surface, anyway—a matter of living somewhere that aligned with the core values and culture of their family, and I’m not sure I can find any fault with that impulse. We all want that.

Of course, being a “political refugee” can also mean something as serious and literal as a life or death decision. The policy landscape on abortion law has been thrown into chaos since the Dobbs ruling in 2022, and women who might need treatment are responding accordingly: doctors and other medical professionals are leaving states like Idaho for greener pastures where they can practice freely; reproductive healthcare is an active factor in students’ college decisions.

It was no different for the earlier-mentioned Noble family, whose transgender son would have had to forgo—or work ten times as hard to receive—the medical treatment he needed for his transition:

“We’ve been here our whole lives,” Ms. Noble said before the move. “Our families are here, friends are here, jobs are here. But when it came down to it, we have to support our son. We have to keep him safe.”

Are these decisions partisan? Are they “political”? Maybe directly and actively; maybe only by happenstance because of “sorting”. Either way, it’s clear that our two major parties are deeply polarized based on geography; but it hasn’t always been this way, and doesn’t always have to be. Until then, at least we have a handle on how we got here.

Thanks for reading! I have two final pieces of news this week; one bad and one good. The bad news is, I’m not doing a newsletter next week because it’s Christmas. Bah humbug, I need a break. The good news is, I’ll be back sooner than you think, because I’m moving my publication day to Tuesdays! This will give me more time to use my Fridays—which are the days I cordon off from my regular job to work on this hobby project—more effectively for the next post. So I’ll see you all in in 2024, where poetry, politics, and of course Taylor Swift appreciation posts await you eagerly. Cheers.

You should, too—it’s absolutely fascinating.

Dear Charlie, Hello from Nampa, ID. I followed you to your substack from your post on the Culture Studies classifieds. My partner and I moved to downtown Nampa in 2013 from the coast in Los Angeles (Hermosa Beach).

I read this article with great interest because I would dearly love to move again but my partner says he's not interested in investing a couple of years to the upheaval and disruption that moving requires. He's 79, and I can see his point. I doubt that we'll be leaving. My children and grandchildren live in Seattle, Vancouver WA, and Portland.

We gradually retreated from community involvement here in Nampa beginning with the Trump years and then abruptly halted with the arrival of the pandemic. I miss the engagement but feel so out of place now.

I think our experience would be so different if we'd moved to Boise instead, but Boise commercial property was out of our budget even back then. We own a sweet storefront near the beautiful Nampa train depot.

We didn't think the politics mattered much when we got here, but things have changed. Not only in Nampa, I know. We hope to come into Boise more often and spend time with more like minded friends--there are more of them in Boise than in Nampa.

Thanks for a place to tell my story 😉. I'm not very political, perhaps because of my immigrant family culture--lots of colonial patriotism that feels way too weird to me. Still thinking about how to sort THAT out, too!

Betty