School can't get us away from politics

But it can remind us of the resilience and grace that politics so often lacks

Just about every year of my life around this time, I’d begin to have the nightmares. They would come around like clockwork. I go to sleep in late August, and am dropped unceremoniously into school, about three-quarters of the way through the semester, and — shocker of shockers — I haven’t been to one of my classes the entire year, and it’s my performance in this class that will determine whether I graduate or not, and not graduating is not an option because then everyone will know I’m a fraud.

Why haven’t I been to class? Why aren’t my friends concerned? Why, when I get to class, does my teacher not say “Hey, I haven’t seen you all semester, what the hell?” It’s a dream, so nobody knows the answers to these questions; but also, it’s a dream, so we don’t need to. Like any dream, it has its disjointed trappings of reality while, at the same time, making utterly no sense at all. My classmates are a hodgepodge of characters from elementary and middle school; my teachers and the building are from high school; and the class is usually something like Anthropology, which I did in fact take for one semester in college, and (sorry) remember nothing about.

I know I’m not the only one who has dreams like this. For me, it was their stubborn persistence over such a long period of time that made me really begin to stand in awe of them, rather than simply loathe them (though I did). The likeliest explanation for their consistency: I went to school a lot, and for a long time. With the exception of a brief but clarifying three-year stint as a political consultant after college (during which the nightmares needlessly continued), late August meant that a new school year was on the horizon for about 25 uninterrupted years.

Old habits die hard, but when I finally finished my PhD in 2019, I made the foolish assumption that since I was no longer a student, the August nightmares would come to a close. They did not. I was and am, after all, a professor: I just keep going to school. Why should my nightmares about attendance emergencies not mutate into ones about grading emergencies?

Strangely enough, it was probably the pandemic that finally broke the cycle. I guess when your life morphs into one continuously-repeating cycle of stress and concern, the back-to-school jitters fade into the background. More tangibly, I taught exclusively over Zoom for almost two full years, which tidily removed the acute fear of in-classroom failure. Zoom, of course created plenty of its own nightmares.

But nightmares, as we know, come in many forms; and they’re more real to some of us than others. Today’s poem features a small but meaningful instance of back-to-school-related fear, shame, and embarrassment — one I’ve never had to face.

On Listening to Your Teacher Take Attendance

by Aimee Nezhukumatathil

Breathe deep even if it means you wrinkle

your nose from the fake-lemon antiseptic

of the mopped floors and wiped-down

doorknobs. The freshly soaped necks

and armpits. Your teacher means well,

even if he butchers your name like

he has a bloody sausage casing stuck

between his teeth, handprints

on his white, sloppy apron. And when

everyone turns around to check out

your face, no need to flush red and warm.

Just picture all the eyes as if your classroom

is one big scallop with its dozens of icy blues

and you will remember that winter your family

took you to the China Sea and you sank

your face in it to gaze at baby clams and sea stars

the size of your outstretched hand. And when

all those necks start to crane, try not to forget

someone once lathered their bodies, once patted them

dry with a fluffy towel after a bath, set out their clothes

for the first day of school. Think of their pencil cases

from third grade, full of sharp pencils, a pink pearl eraser.

Think of their handheld pencil sharpener and its tiny blade. I wonder if — as a professor herself — the poet Aimee Nezhukumatathil (pronounced, by the way, “Neh-zoo-koo-muh-tah-til”) has had the same kinds of back-to-school nightmares that I did. She’s definitely more impressive than I am: in 2014, she was one of the country’s youngest poets to ever achieve the rank of Full Professor of English (I haven’t even reached Associate yet).

But as the poem’s inciting incident makes clear, our rank isn’t the only thing that sets our experiences apart. Nezhukumatathil was born in Chicago to a Filipina mother and a father from South India. With that kind of last name, I am willing to bet that this was not just one difficult instance of embarrassment, but a lyrical merging of a lifetime of them, repeated yearly on every first day of school like my nightmares, only real. The displacement from the poet’s name and her culture that plays out here is, she says, small — a “tiny blade”, maybe — but it naturally hurts nonetheless.

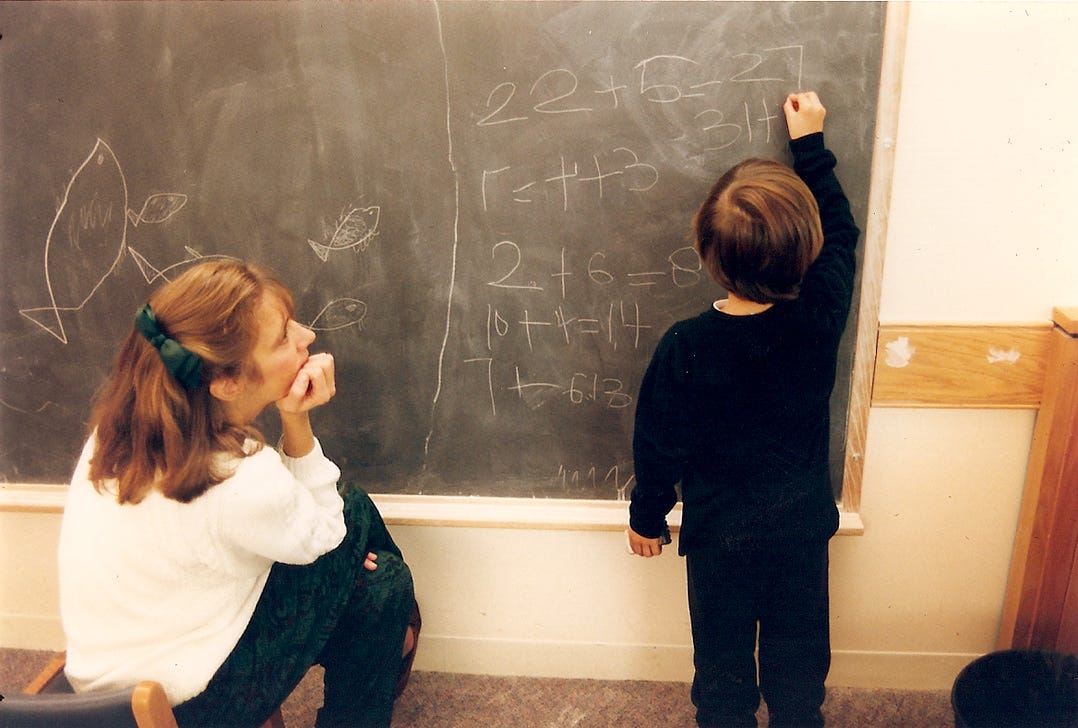

No matter how jubilant and ready to learn the kid actors in the JC Penny “back-to-school-doorbuster” ads may appear, walking back through those doors comes not just with excitement, but huge social and intellectual complications.

At school, we’re surrounded by books and peers and authority figures, the breeding grounds for sociocultural thriving and dynamism; but also misunderstandings, and sometimes embarrassment and shame.

These misfortunes are usually intertwined with our politics, whether we like it or not. In fact, many of the political issues that we most associate with schools are indisputably among our most contentious: school shootings, mask mandates, how we teach controversial topics like race and gender; the interminable panic over where trans students might deign to use the restroom; and even, apparently, whether schools should provide period care products to students who might not be able to afford them.

These political issues may feel abstract sometimes, but they manifest in more personal, individual injuries. The terror of gun violence doesn’t (thank God) rear its head for every student, but a fair many of them suffer the indignity of the active-shooter drill. Schoolwide controversies over race relations might not engulf a majority of student bodies, but the teacher may still badly fail at pronouncing your multiethnic last name during attendance, when that name emblemizes a cultural heritage that means the world to you. No matter how much we might like it to be, and no matter how much parents may wish school to be a politics-free-zone, it’s simply not an option, even if (like me) you have the luxury of a typically white name.

My own experience of how school and politics intersect is not so culturally fraught and personal as Nezhukumatathil’s, and I can’t emphasize enough that I’m not directly comparing them. The back-to-school frictions I’m confronting this very week are, however, even more on-the-nose when it comes to American politics.

Summer 2024 is not even technically over yet, but has featured just about the wildest and most unpredictable series of political events of my lifetime. The first felony conviction (34 of them, in fact) of a former president; a debate between that man and the current president that went so badly that one of them had to drop out; the replacement of that candidate with the first nonwhite woman to lead a major-party ticket; two party conventions; oh, and an assassination attempt, not to mention a maelstrom of deeply disturbing Supreme Court opinions.

This is the kind of summer that could reasonably leave a person (at least one who pays close attention to politics) needing a break from their summer break. I’m guessing some of you feel this way. The prospect, then, of heading back to school in the fall — something predictable, and with reliable symbols and hallmarks from year to year (the “mopped floors and wiped-down/doorknobs”, the “handheld pencil sharpener”) — might feel to many like finding your way back to solid ground after going on that psychotic ride Tim Walz and his daughter rode at the Minnesota State Fair.

But alas, not for me: I have a unique profession in which the election, its causes, its outcomes, and its consequences are nonnegotiable elements. My job, literally, is to stay on the roller coaster, because I’m apparently in charge of teaching tomorrow’s leaders how the roller coaster works. Not only am I a political science professor, but I’m teaching two different courses on American campaigns and elections this fall. Taking a break from the news, or escaping the election entirely, or “sitting this one out” for the sake of my mental health would mean not doing my job.

I don’t want to sound too sorry for myself, mainly because I love my job, and wouldn’t trade it for any other, even on its worst days. But also because today’s poem has lessons and reminders that I’ve been able to try and take with me, even if I haven’t faced these same cultural indignities.

One could read this poem and see the unfortunate microaggression by itself as the central point. To me, the much more important takeaway is the combination of grace and resilience with which Nezhukumatathil internalizes and address it. She forgives, immediately, the teacher who butchers her last name (“[he] means well”); she pictures her staring classmates in more innocent and delicate moments rather than the judgmental one they’re in now. True, these might just be gestures to make her classmates less threatening, to neutralize their stares by picturing them as helpless. But I think we can also interpret that she’s trying to see the best in them, remembering to give them grace because they, too, were once held delicately by their parents after a bath; they, too, opened up their pencil cases in third grade, “full of sharp pencils, a pink pearl eraser,” and found something known and comfortable.

What could this mean for my classrooms today? “Resilience and grace” are not exactly the watchwords of our politics, certainly not in an election year. I know that. Seeing the best in each other, especially those who (we think) threaten us, is more difficult all the time. More news and comedy segments seem dedicated to mocking those who don’t think like us than trying to understand them, much less offer them grace and dignity.

Meanwhile, Nezhukumatathil shows us how to use things she cherishes about her culture (memories of “baby clams and sea stars” in the South China Sea) to help weather its difficult parts. Although I often fail at it, this is precisely my strategy with American politics, with which I am in a relationship fraught with both love and complication.

But I know that I’m at my best in the classroom — and that my students will be the beneficiaries — when I can embody and reflect the things that I love about politics and government and elections, and not just the difficult parts that drive everybody crazy. This is what I see in my students, who are nearly always trying to think of ways that politics and government can improve, because they know what I know: that when politics drives me nuts and burns me out, it’s only because I care about it deeply and know how much meaning and dignity it can give us when its at its best.

Am I still desperately trying to structure my weekends to focus on other parts of my life? You bet. But in the meantime, the only path forward is accepting that disengagement is not an option — and finding what beauty I can in that fact.

the summer political season has been a bit exhausting even to those of us for whom it isn't our job