7 reasons why Elon's new party is over before it starts

Without fundamental change to our system and our politics, centrist parties are pretty much doomed to fail

As just about everyone predicted 6 months ago, the love connection between Elon Musk and Donald Trump has, by all accounts, been irrevocably shattered. Between the DOGE cuts, the weird Oval Office press conferences, and the various accusations of pedophilia and drug abuse, it sure has been a wild ride.

But the wild ride apparently is not over. After calling out Trump’s “One Big, Beautiful Bill” that was just signed into law as a fiscal abomination, Elon has vowed to start a new political party dedicated to fiscal discipline, along with… we’re not really sure what else yet. "You want a new political party and you shall have it!" Musk said in a post on his fetid sinkhole social media platform, X. "When it comes to bankrupting our country with waste & graft, we live in a one-party system, not a democracy. Today, the America Party is formed to give you back your freedom."

A party besides the Democrats and the Republicans. Why didn’t I think of that!

To be fair to Elon, a few nationwide trends have been unfolding over the past 20 or so years that, if you’re aiming to jumpstart a third-party movement, would be very promising. Gallup, for example, regularly polls Americans on whether they think the Republican and Democratic parties are doing an adequate job; or, if the two parties are screwing up so badly that a third major party is needed.

The chart speaks for itself. This is not just a clear majority of Americans who say they want another party, but a majority sustained over the past ten-plus years of American politics.

You’d be even more motivated if you saw the next chart, which shows a very similar trajectory: that not a majority, but at least a vast plurality of Americans do not identify first and foremost as Democrats or Republicans, but as Independents, and that this gap is as high as its ever been in modern political history.

These charts appear to tell a pretty clear story: not only do Americans say they want a third party, but this party is bound to be successful because of how significantly they outnumber both Democrats and Republicans.

Unfortunately, this story has the same problem as Elon’s quest to colonize Mars, which is that — at least right now — the story is much closer to science fiction than actual reality. It’s a lie that egocentric politicians (and wannabe politicians) who don’t understand American politics tell themselves in order to convince themselves of their own importance. I’m looking at you, Joe Lieberman (RIP); and you, Andrew Yang; and you, Michael Bloomberg.

But, it’s also a story that many Americans who are frustrated with the state of our politics tell themselves as well; and so it’s important to take this seriously. So, let’s break down why Elon’s “America Party” is likely to explode on the launchpad, and what would need to be different in order for any third party to become viable nationwide.

Whole books have been written about the ill-fated nature of third parties in the United States, so I’ll spare you a full rewrite. Instead, I’ll go with the tried-and-true 7-item “listicle” to make sure I don’t ramble on too long.

Here we go:

1. Not everyone wants the same “new” party.

The first chart I shared above seems to tell us that a very comfortable majority of Americans want a new party. But that chart does not tell you what kind of party those Americans want.

Some of the Americans responding “yes” to that question might want a centrist or middle-of-the-road party; say, a Mitt Romney type. But others are Bernie Sanders-style socialists, or Libertarian isolationists, or MAGA folks who are so extreme that they want to abandon the Republican Party for being too squishy.

The bottom line: the 60-ish percent of Americans who say they’d like to see another party enter the scene have very little agreement on what that party should look like. Good luck organizing all of them to vote for the same candidates!

2. “Independents” aren’t all that independent.

The second chart I showed you is also really misleading. It shows you only the answer to the first question pollsters typically ask about party affiliation: whether respondents think of themselves as a “Democrat”, “Republican”, or “Something else/not sure”.

But then pollsters ask a follow up question of that third “Something else” group. Essentially they ask which of the two major parties they’d lean towards if they had to choose between them. The chart below is (I would argue) the more accurate version, which shows the balance between the three groups if you include these “leaners” under Democrat and Republican party totals.

What does this mean? That about 9 out of 10 so-called “independents” give up the game immediately when asked to share which party they tend to lean towards, and thus aren’t nearly as “unaffiliated” as they and we might think.

This matters because these “leaners” have remarkably similar voting patterns and ideological preferences to those folks who answered “Democrat” or “Republican” on the first try. In 2008, for instance, 92% of voters who classified themselves as “Strong Democrats” voted for Barack Obama. Meanwhile, 91% of Democrat-leaning Independents also voted for Obama. They were basically indistinguishable, and that pattern has held up over time.

In short: these “leaning” voters — who make up a solid quarter of the voting population — might not love the two major parties, but they don’t seem to be in search of a party that has radically different ideas than the ones we already have.

3. The actual “middle” isn’t just small: it’s mushy.

In musing about this new party during one of his online tirades against Trump, Elon declared that it was "time to create a new political party in America that actually represents the 80% in the middle." We’ve already dispelled the notion that “the middle” constitutes 80% of the electorate. It just doesn’t. People like to think of themselves as centrist, but way fewer people than we think actually are when push comes to shove.

Beyond that, even the actual “centrists” look really different from each other. Some people might have “moderate” views, essentially by splitting the difference on every issue in American politics between the Democrat and Republican positions.

But others have not so much moderate, but rather “mixed” views on the issues. Maybe someone’s a hardliner, Stephen Miller-style immigration hawk, but is also a zealot in favor of strong union representation and wants Medicare for All. There really are voters out there who want to legalize weed, ban books with transgender characters, open the borders completely, privatize social security, and install solar panels on the White House roof, all at the same time.

These Americans have what we would call “incongruent” or “cross-pressured” beliefs that don’t fit the traditional two-party position-taking we’re used to. Other Americans have what we would call “inconsistent” beliefs; meaning, their stances on issues are super malleable, and liable to change as our nation and politics change. None of these people can’t really be called “centrists”, but they do exist. I usually refer to them collectively as the “Joe Rogan” archetype.

Alexander Burns, a journalist and head of news for Politico, summed up nicely this possible opportunity for Musk:

Musk’s plan can only work if he learns from the most successful political disruptors, including Trump on the right and Bernie Sanders on the left, and identifies places where both political parties are neglecting the real preferences of voters. This means not finding a midpoint on a left-right spectrum but rather seizing issues beyond the standard D-versus-R menu.

I think this is right (if even a little optimistic), in the sense that the likeliest new parties to emerge in American politics are the ones on the fringes, rather than the muddy center. But this is partly because…

4. The most intense partisans are the most engaged in politics.

Sad and unfortunate? Maybe; but it’s true. Voters who most strongly identify with one of the two major parties are the most likely to vote, donate, and participate in politics. They follow politics closely, have strong views about it, and act accordingly. Americans who think of themselves as “Strong” Democrats or Republicans made up 52% of the electorate in the 2016 election, but only 19% of the group of Americans who didn’t vote. Meanwhile, those “Pure Independents” — the ones who refused to even lean towards one of the two parties — were only 10% of the voting population, and nearly a quarter of all those who didn’t vote.

What this means is that the group of Americans who are most likely to be dissatisfied with the two major parties in favor of a middle-of-the-road America Party is the same group of folks who are going to be most difficult to organize around one big, beautiful new party mantle.

5. Elections are hard.

Besides all these demand-side problems, third parties also face huge legal and procedural obstacles before they’re even included in the formal electoral process. Ballot access laws are stringent, and usually require thousands or tens of thousands of legitimate signatures from regular people to even get a party on a ballot. Third parties are nearly always excluded from candidate debates at all levels, and the news media doesn’t tend to take them seriously. They also face difficulty in fundraising, which further marginalize them.

Even one of Musk’s big advantages in this area — his basically limitless wealth — can only get him so far. Of course you’d rather have the money than not; but fellow billionaires like Michael Bloomberg and Tom Steyer have showed us that you can’t make voters be interested in you or your ideas. Our campaign finance system may be so permissive as to be a joke, letting people like Musk spend the many hundreds of millions he did in 2024 to help get Trump elected; but as of yet, it can’t literally buy the votes or ballot signatures needed to create the kind of nationwide movement necessary to compete with the Democrats or Republicans.

6. Elon Musk is a very imperfect standard-bearer for a new party.

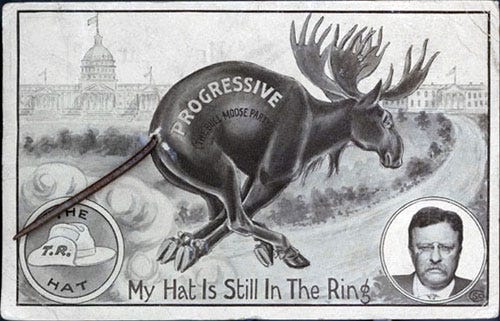

Most third parties that have achieved any modicum of success have been ones with charismatic and popular standard-bearers: Ross Perot and Jesse Ventura for the ill-fated Reform Party won quite a few actual votes. As a former president, Teddy Roosevelt very nearly won a third term in 1912 with his progressive “Bull Moose” party after previously serving as a Republican.

But Teddy Roosevelt this guy ain’t. For one thing, Musk is horribly unpopular. For another, he’s not constitutionally eligible to run for president since he was born in South Africa, and not to American parents. For still another, I’m sorry, but the guy is not exactly a charisma machine. If this effort is ever going to be successful, he needs to follow

’s suggestion and focus all that wealth on research and recruitment of potential candidates who have the political and public-facing acumen Musk so severely lacks.7. Our system of voting is inhospitable to third parties.

Even if many of these first 6 items weren’t the case, there are still fundamental elements of the way we vote in most elections — which are enshrined in state and federal laws and constitutions — that make the two-party system more or less inevitable, especially after the polarization that’s taken place in the U.S. over the past 50 years.

This inevitability is summed up in a term from political theory called Duverger’s Law, which argues that single-member district plurality systems — where only one candidate wins in each district and the winner is the one with the most votes — naturally and inevitably lead to a two-party duopoly.

The reason? Because in our system, third party candidates are destined to be spoilers. At least at the federal level, only one person can win any given election, so voters are reluctant to “waste” their vote on a third-party candidate who is unlikely to win. Instead, they often choose the lesser of two major-party evils. And the more polarized we get, the more we fear the possibility of the “other side” winning; and thus, the more gun-shy we get about rolling the dice on a third party candidate, particularly for offices like President and Congress. Just ask the few but decisive folks who voted for Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein in 2016 rather than suck it up and vote for Hillary Clinton.

At the end of the day, both voters and political elites behave strategically. Voters back major-party candidates instead of outliers to avoid helping their least-preferred option, and elites (e.g., donors, activists) concentrate their resources where they have a realistic chance of winning — with the two parties.

As

puts it wonderfully in his go-to book on the subject, “Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop”, this is all unlikely to change without major, fundamental reforms to how we vote in this country.

“So, let’s break down why Elon’s “America Party” is likely to explode on the launchpad”

Fantastic stuff